Smart cities are emerging as major engines for deploying intelligent systems to enhance urban development and contribute to the UN 2030 Sustainable Development Goals. The rise of smart city initiatives is not only seen in North America and Europe but also increasingly in Asia and across the developing world which faces rapid urbanization and technological change. Home to the UNU Institute in Macau, the city of Macau is a special administrative region (SAR) of China where “the East meets the West” in local governance, economy, and society. Our research article, recently published in the Journal of Urban Affairs, offers first-hand accounts of smart city development in Macau. This blog post highlights some of the findings and recommends policy changes to help propel the city’s future smart transformation.

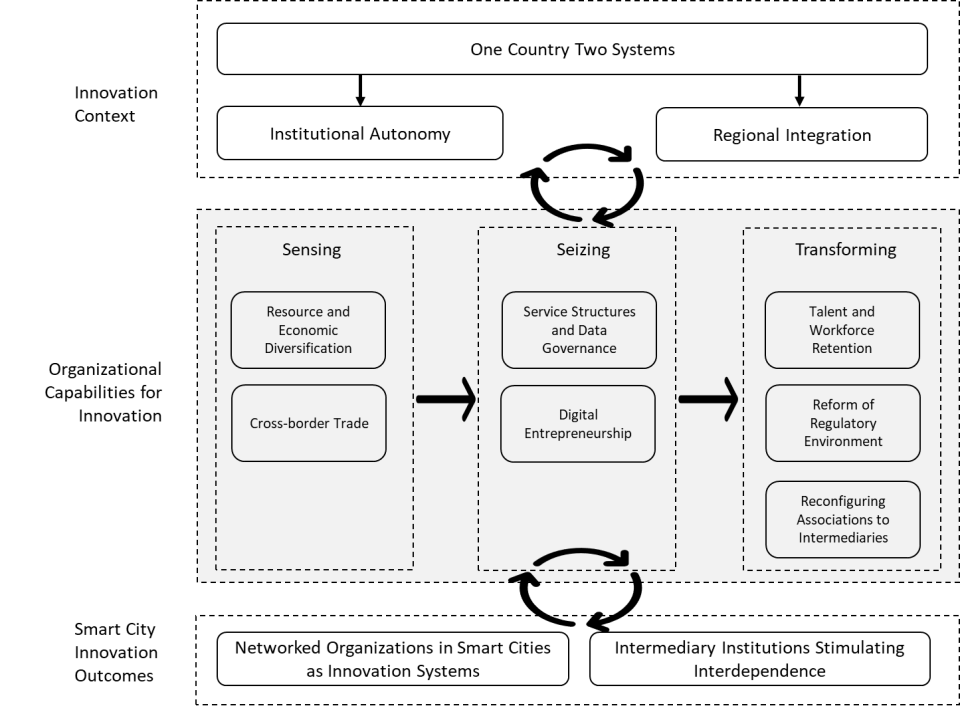

In smart city initiatives, a system thinking approach to innovation, with a focus on the institutional contexts and the resultant institutional capacity for innovation and the role of public-private partnerships can be useful. While technology is crucial to achieving competitive innovation capabilities, the development of digital technologies exists within peculiar social, economic and political institutional contexts. In the case of Macau SAR, the unique context of “One Country Two Systems” has defined the city’s development trajectory and allowed the city a relatively high degree of autonomy from the mainland China, while regional integration has been deepening.

A former Portuguese colony and now special administration region (SAR) of China, Macau is a densely populated city, with about 700,000 residents on just 32.8 square kilometers of land. Following the end of Portuguese rule and handover to China in 1999, Macau government ended the monopoly of casino gaming rights, so the gaming sector was able to expand rapidly, under the influx of both foreign investments and mainland Chinese visitors, to the only city operating casinos legally in China. The city enjoyed a rapid economic boom, reaching the second highest GDP per capita in the world in 2019. Yet along with the structural change towards an economy dominated by casino gaming and tourism, traditional industrial sectors had rapid contractions, the city’s public resources were under increasing strain, and issues such as environmental degradation, traffic congestion, small business failures, and gambling addiction have worsened. This led to rising fear about the long-term sustainability impact on Macau’s economy, citizens’ wellbeing, and governance. The COVID-19 pandemic indeed demonstrated the urgency of resource and economic diversification into more value-added sectors, as travel restrictions and lockdowns resulted in drastic revenue decrease from gaming and severe economic downturn. Macau’s smart city ambition, first stated in the government’s first five-year plan (2016-2020) and further solidified in the current five-year plan (2021-2025), can be therefore viewed as part of its strategy to strengthen the city’s governance and strive for long-term sustainability and prosperity.

From a broader spatial lens, Macau’s smart city development fits into China’s Guangdong-Hong Kong-Macau Greater Bay Area (GBA) development planning, which seeks to deepen the economic and social integration of the Pearl River Delta region, bringing in Hong Kong and Macau, two SARs with distinctive local institutions under the “One Country Two Systems” principle closer to mainland China. The GBA plan unveiled by the central government of China in 2019 calls for developing a world-class bay area, including a smart city cluster by 2035 and strengthening cross-border collaboration across areas of trade, infrastructure, data governance, transport, energy, municipal management. Yet as Macau still falls behind other cities in the GBA region in technology industry development, enhancing Macau’s advantage and mitigating existing problems is crucial to maintaining Macau’s competitiveness as a future smart city in the region.

Drawing on fieldwork interviews and secondary data and adopting a capabilities lens, we further developed a stage-based assessment of innovation capabilities related to the use of technologies in Macau’s smart city development, characterized by specific city-level innovation capabilities: sensing, seizing and transforming (shown in Figure 1). We found that local public and private players quickly began developing systems to learn to sense and calibrate new opportunities for diversification and for cross-border economic collaboration. For example, Macau Pass is a mobile payment platform with e-wallet service called MPay, founded by a local family business also running public buses and digital media networks, before acquisition by mainland China’s Alibaba in 2022. The platform has expanded e-payment across the city, connecting local banks into its payment networks and developing a network of residents, visitors, service providers, merchants in Macau and with business partners in the Greater Bay Area. Service structures to enable the government and businesses to develop further capabilities and promote regional connectivity were created. For example, the government through an agreement with Alibaba Cloud established a cloud computing center, expediting data sharing among agencies in areas such as transportation, tourism, and medical services, and enhancing one-stop public service platform for residents.

Towards smart cities as innovation systems, cities require the development of intermediaries that facilitate network creation and expansion, knowledge sharing, and coordination among stakeholders. This enhances the capabilities of the stakeholders that own complementary assets associated with the process of coordinating, redeploying, and leveraging resources for innovation in a smart city. Intermediaries can perform important functions within the peculiar innovation contexts, such as information collection and exchange, network development, relationship building, and collaboration among players in the innovation system. In the case of Macau, the intermediary role of local associations, entrepreneurship incubators and digital platforms facilitating coordination among players is evident. Entrepreneurship incubators, such as the government-funded Macau Young Entrepreneur Innovation Centre, and several university- or privately-funded accelerators serve as intermediaries mobilizing resources and connecting aspiring local tech entrepreneurs with public and private organizations in Macau and across borders in the GBA region and overseas. Local associations served as mediators of governance between the Macau public and the Portuguese colonial administration, and post-handover continued to serve as important intermediaries in Macau’s society. In Macau’s smart city initiatives, associations have also performed some governance functions by socializing, mobilizing and sharing resources where existing government capacities are constrained. Associations acted as conduits for policy dialogues among the government, firms and other stakeholders, by conducting research, participating in relevant city government committees, negotiating policy changes with agencies and legislators, organizing outreach events, sharing resources across associations, and facilitating connections of local players with organizations located in the GBA region and overseas.

While Macau’s smart city development has seen noted progress, we found that the innovation system is still struggling to achieve complementarity among stakeholders. As Macau moves into the next phase of smart city development, we recommend that policymakers develop a comprehensive strategy that includes a mix of policy levers and funding strategies for workforce development and retention, regulatory reform, public participation, knowledge transfer between R&D players, and infrastructure development. Some recommendations are as follows:

- To support the development of emerging technologies and digital entrepreneurship, the government needs to develop agile regulations for technology and data use, break down data silos and promote open data and knowledge sharing among the government agencies, and between the government, the firms, universities, and other stakeholders within Macau to promote open innovation, and further stimulate cross-border partnerships with players in mainland China and overseas.

- To alleviate the talent shortage, the government should enhance public-private collaboration in identifying and meeting workforce needs, enlarge the local tech talent pipeline, and make the city an attractive place for talent immigration.

- To promote the local players’ awareness and engagement of smart city initiatives, the government should strengthen open and effective public engagement through local associations, platforms and entrepreneurship incubators as intermediaries, promote knowledge sharing between universities and private-sector R&D players, and enhance digital literacy of the general public.

- To enhance Macau’s attractiveness and regional connectivity, continued investments in urban infrastructure and sustainable urban environment, such as transport and telecommunications networks with affordable options for local citizens and firms are necessary to promote human-centered innovation and attract talents from elsewhere.

- To achieve the sustainable development goal of “leaving no one behind”, the public and private sector entities need to provide financing and technical support to civil society groups providing social services, and through them engage more local citizens including vulnerable populations such as youth, women, and the elderly, enabling them to play a stronger role in collaboration for innovation.

Yujia He, Assistant Professor, Patterson School of Diplomacy and International Commerce, University of Kentucky & Visiting Fellow, UNU Macau (July-August 2023)

For extended reading, please visit the video: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=nH_eV_4A52Y

Suggested citation: Yujia He., "Towards Smart Cities as Innovation Systems: The Case of Macau SAR," UNU Macau (blog), 2023-09-01, 2023, https://unu.edu/macau/blog-post/towards-smart-cities-innovation-systems-case-macau-sar.