The complexity of climate change impacts makes it difficult for decision makers to translate scientific findings into effective policies. To address this challenge, the UNU-EHS Enhancing Risk Assessment (ERA) project team together with GIZ, the German agency for international cooperation, developed a new framework that expands how climate risks are assessed. Beyond financial losses – such as damage to infrastructure – the approach also considers non-financial impacts, including effects on health, mobility and access to essential services, as well as macroeconomic factors like GDP and employment.

Built on the open-source tools CLIMADA, the modelling platform underpinning the Economics of Climate Adaptation, and the Climate Resilient Economic Development model (CRED), and guided by the Economics of Climate Adaptation (ECA) framework, the method brings diverse stakeholders into the process and uses the best available data to ensure transparent and credible results.

With the support of national authorities, the approach was applied in Egypt and Thailand, combining multi-hazard risk analyses with cost-benefit assessments of adaptation measures. This provides decision makers with a clearer, more comprehensive view of climate risks and the most effective options to reduce them. In addition to the Thailand case study report, an infographic was created to visualize some of the report findings and illustrate the innovations of the methodological approach. Here are five windows into Thailand’s Economics of Climate Adaptation (ECA) to help break things down:

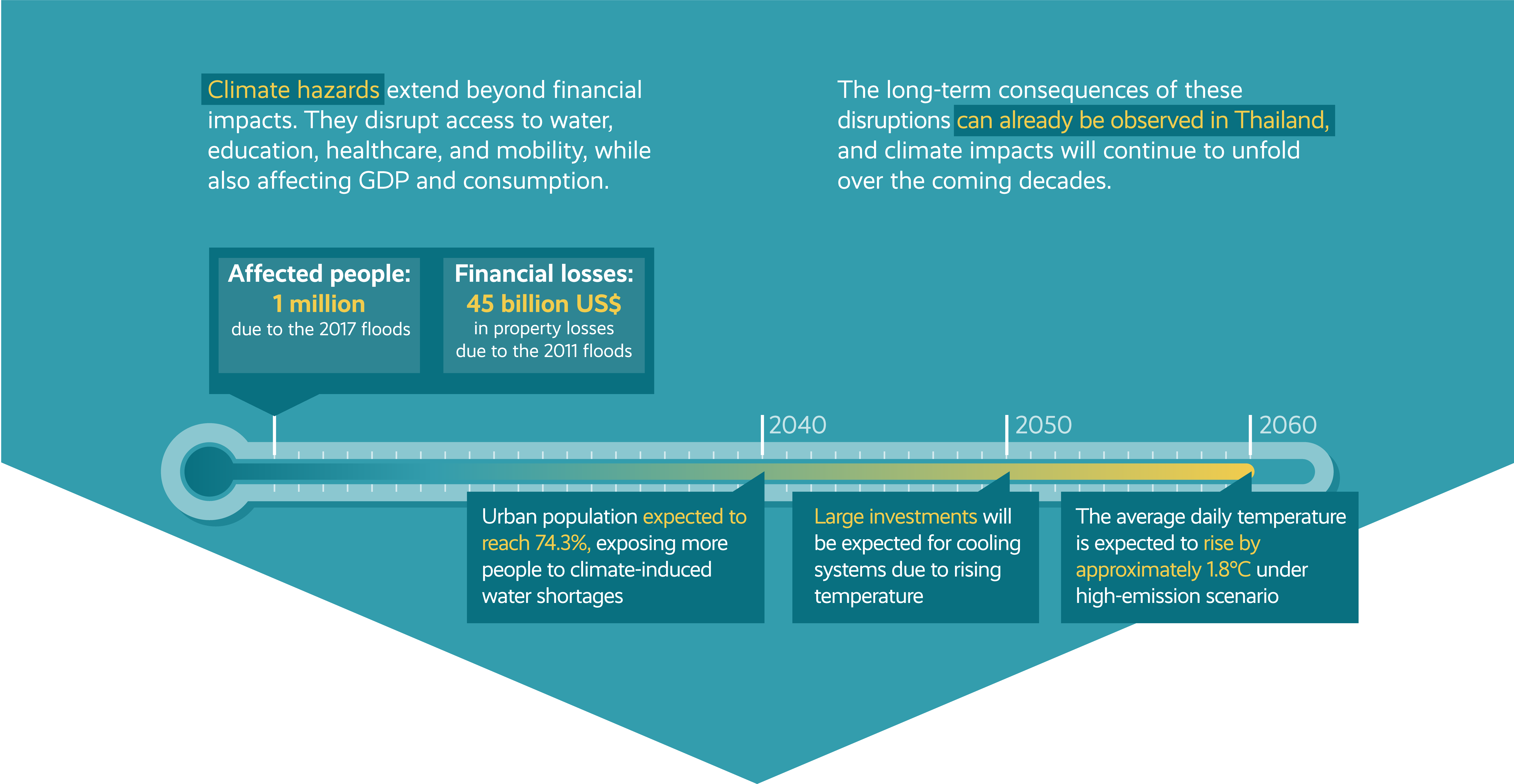

Rising temperatures, rising risks

Thailand is warming quickly. On a high-emission route, the country’s average daily temperature is expected to rise by 1.8°C, which would likely drive up the demand for cooling systems and adding pressure to energy use and household budgets. Climate hazards also leave a costly trail. For instance, the 2011 floods caused USD 45 billion in property losses, and in 2017 another flood event affected 1 million people. Behind these numbers are stories of people losing their homes and livelihoods with communities struggling to recover.

Health impacts reveal the human cost

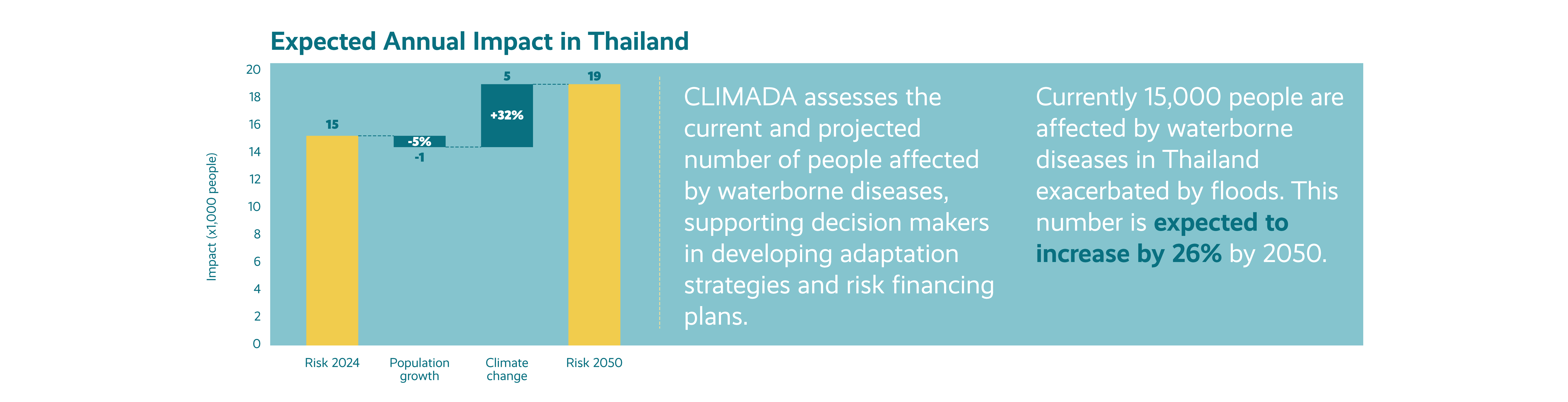

There are also less-visible consequences of climate hazards, such as the rise in waterborne diseases, often intensified by flooding. Today, around 15,000 people in Thailand are affected by such diseases. By 2050, this number is expected to increase by 26 per cent, as flooding becomes more frequent and severe. Climate risks cannot only disrupt daily life but also pose direct threats to people’s health. For communities already living with limited access to healthcare services, these added pressures deepen vulnerability.

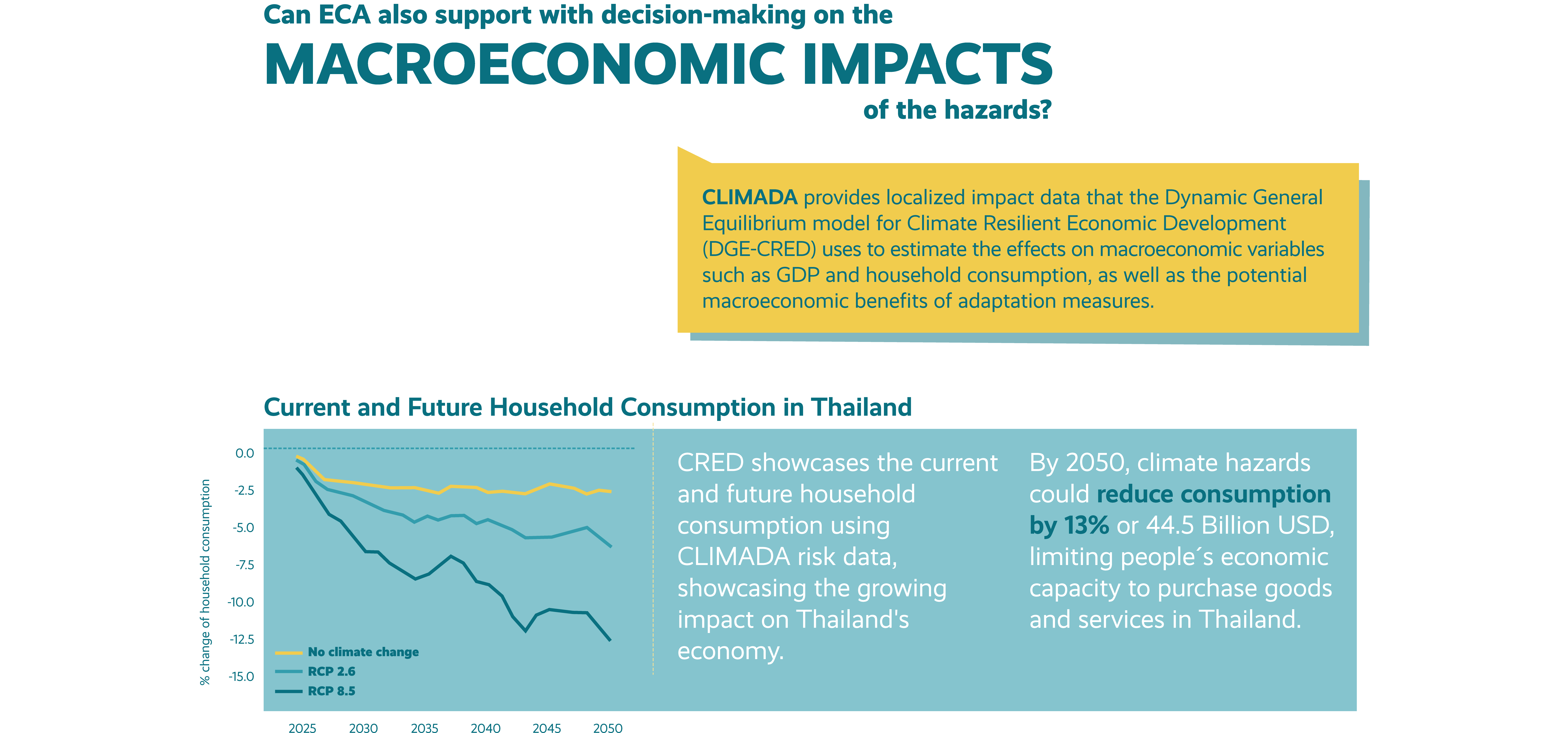

Interconnected impacts across services and the economy

Climate hazards disrupt critical systems all at once, such as water supply, mobility, education and healthcare. These disruptions are more than short-term inconveniences, because they often result in long-term economic consequences. Using localized impact data from CLIMADA, the modelling platform underpinning the Economics of Climate Adaptation (ECA), the Climate Resilient Economic Development model shows that by 2050, climate hazards could reduce household consumption in Thailand by 13 per cent, equivalent to USD 44.5 billion. A decline of this scale means families may have less money for food, education, transportation or savings, showing how climate change impacts affect both national economic stability and daily life for millions of people.

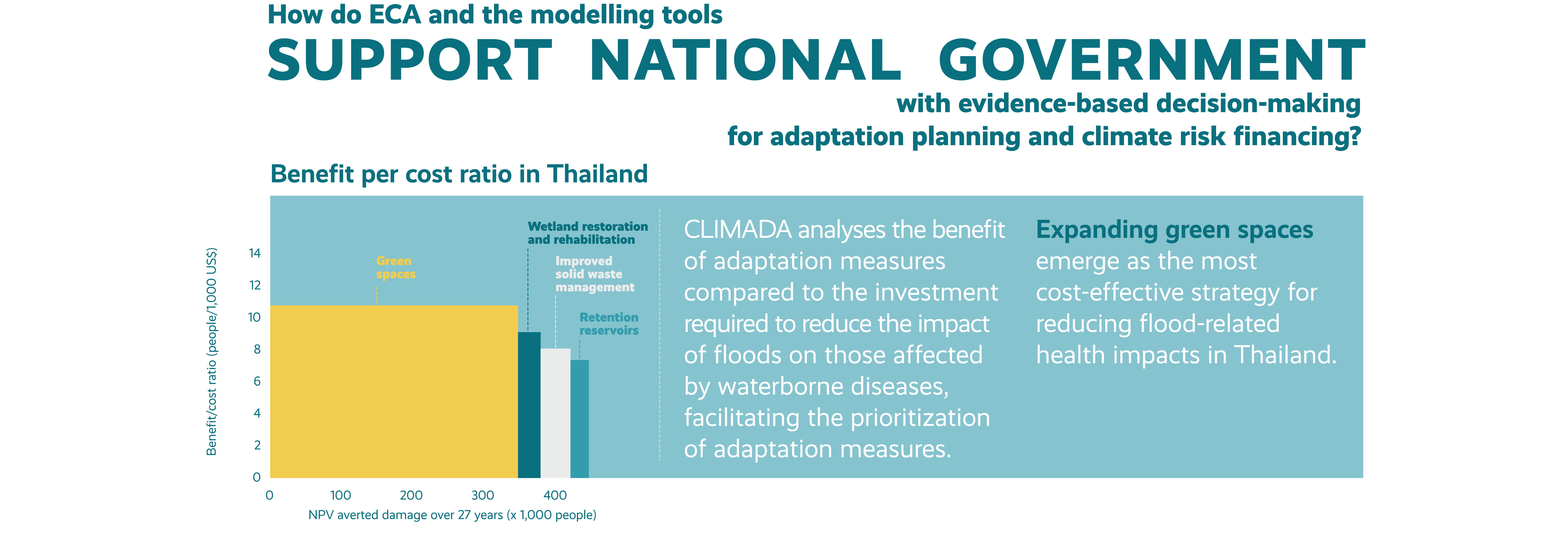

Which adaptation measures make the biggest difference?

To move from impact to action, the ERA project assessed a portfolio of adaptation measures. These include expanding green spaces, restoring wetlands, improving solid waste management and building retention reservoirs. Each option is evaluated by comparing the investment required with its expected benefits. Among them, expanding green spaces emerges as the most cost-effective strategy for reducing flood-related health risks. The graphic also shows the net present value (NPV) of averted damage over 27 years, illustrating how many people could be protected through different interventions. This kind of evidence can support decision makers in prioritizing measures that deliver the strongest and most sustained results.

Understanding Thailand’s future risk landscape

Risks evolve over time when factoring in climate change and population dynamics. The “Expected Annual Impact” graphic reveals that by 2050 population growth could slightly reduce overall risk by 5 per cent and climate change could increase risk by 32 per cent. Taken together, these insights unravel a critical point: climate change is projected to be the dominant driver of future impacts, which is why proactive adaptation matters and is so important. By combining localized climate impact data with economic analysis, Thailand can identify which adaptation investments will offer the most protection, help maintain household consumption and strengthen resilience across essential services.

The complete infographic is available here.