The complexity of climate change impacts makes it difficult for decision makers to translate scientific findings into effective policies. To address this challenge, the UNU-EHS Enhancing Risk Assessment (ERA) project team together with GIZ, the German agency for international cooperation, developed a new framework that expands how climate risks are assessed. Beyond financial losses – such as damage to infrastructure – the approach also considers non-financial impacts, including effects on health, mobility and access to essential services, as well as macroeconomic factors like GDP and employment.

Built on the open-source tools CLIMADA, the modelling platform underpinning the Economics of Climate Adaptation, and the Climate Resilient Economic Development model (CRED), and guided by the Economics of Climate Adaptation (ECA) framework, the method brings diverse stakeholders into the process and uses the best available data to ensure transparent and credible results.

With the support of national authorities, the approach was applied in Egypt and Thailand, combining multi-hazard risk analyses with cost-benefit assessments of adaptation measures. This provides decision makers with a clearer, more comprehensive view of climate risks and the most effective options to reduce them. Based on the Egypt case study report, an infographic was designed to help illustrate innovations of the methodological approach and some of the key results from the analysis. Here are five windows into Egypt’s Economics of Climate Adaptation to help break things down:

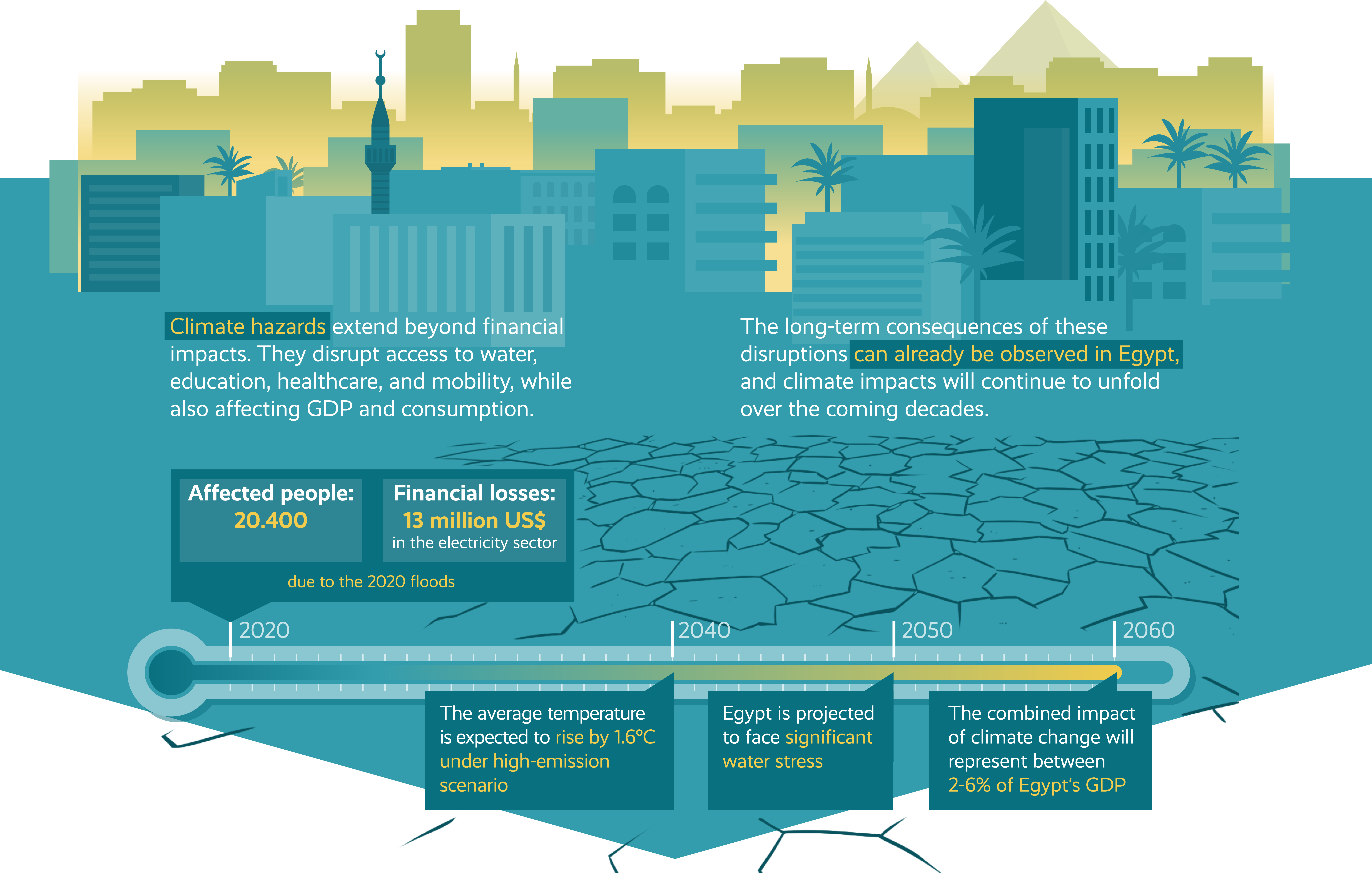

Climate change is already eating into Egypt’s growth potential

Egypt is warming rapidly and is projected to see temperatures rise by 1.6°C, with heat, floods and water stress intensifying in parallel. These hazards already carry a measurable price tag, because the combined long-term impacts of climate change could represent 2–6 per cent of Egypt’s GDP by 2060. What looks like a single line on a graphic is actually a shift with far-reaching consequences for development, livelihoods and national planning.

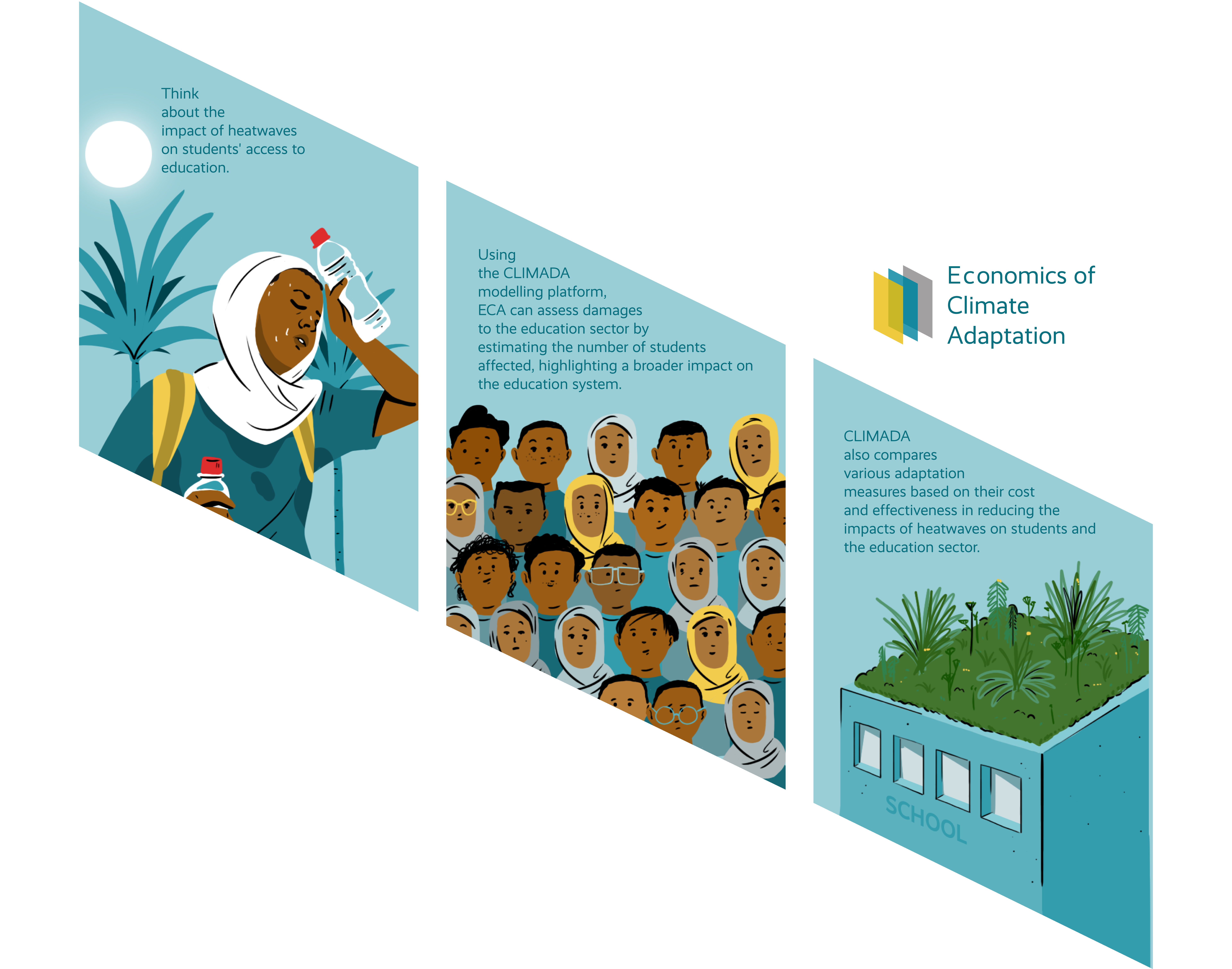

The human reality behind the numbers

In 2020, floods impacted 20,400 people and caused USD 13 million in losses in the electricity sector. But beyond the numbers, one of the most striking impacts are experienced by students. Today, heatwaves disrupt schooling for over 670,000 students every year. By 2050, under a high-emission scenario, that number could rise by up to 72 per cent. Behind those bars and percentages are classrooms that become too hot to learn in, interrupted lessons and students whose futures are shaped by climate stress.

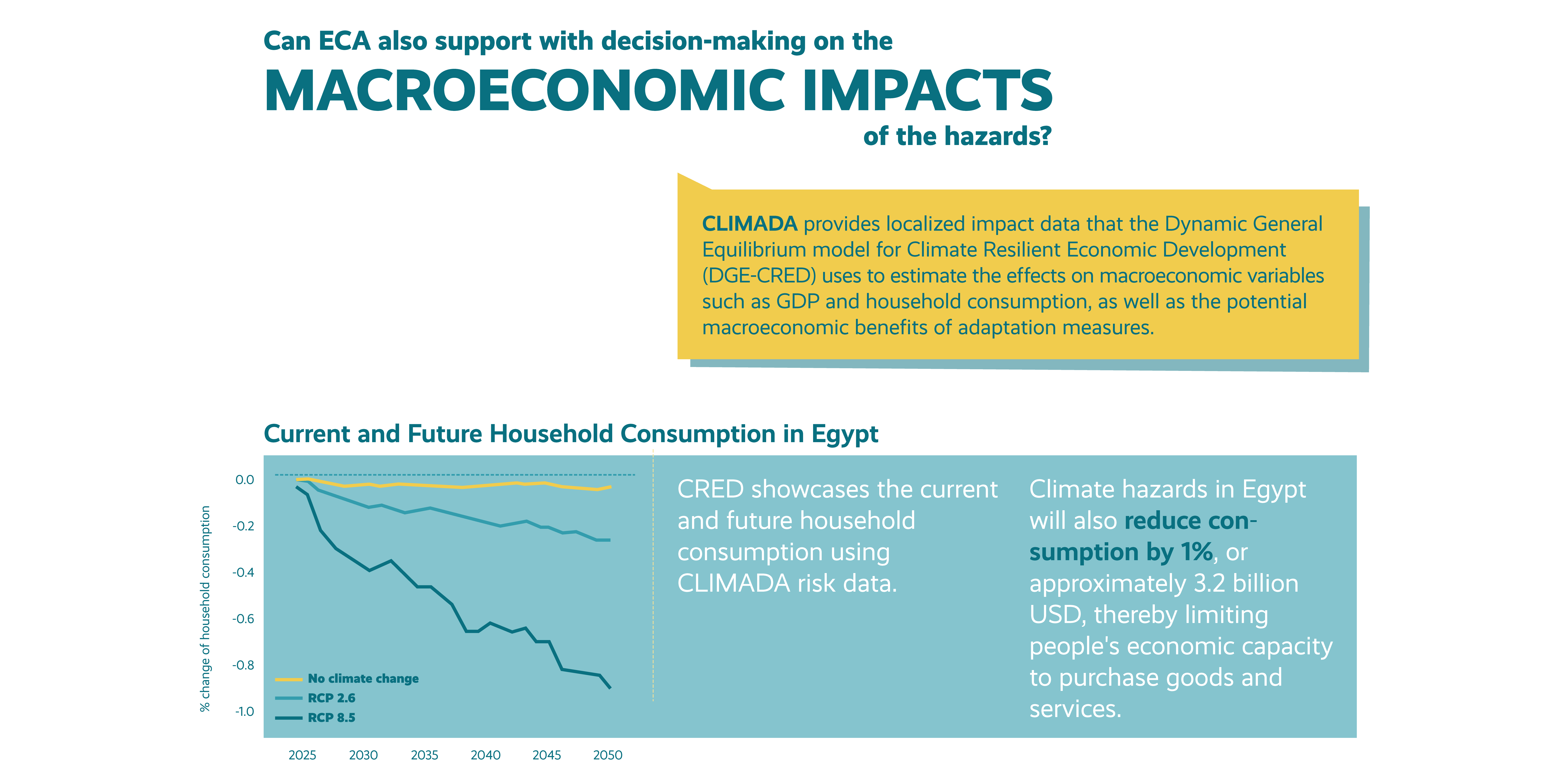

Pressure on systems and services

Climate hazards do not strike in isolation but are interconnected and ripple across essential services. In Egypt, water stress is projected to intensify, mobility can be disrupted and access to education and healthcare can become difficult, if not temporarily impossible.

Economically, these systemic pressures translate into reduced household purchasing power. Using risk data from CLIMADA, the modelling platform underpinning the Economics of Climate Adaptation, the Climate Resilient Economic Development (CRED) model shows that climate hazards could reduce household consumption by 1 per cent, or USD 3.2 billion. Although it sounds complex, this is more than a macroeconomic figure. It means that families have less capacity to absorb shocks, invest in education or pay for essential goods.

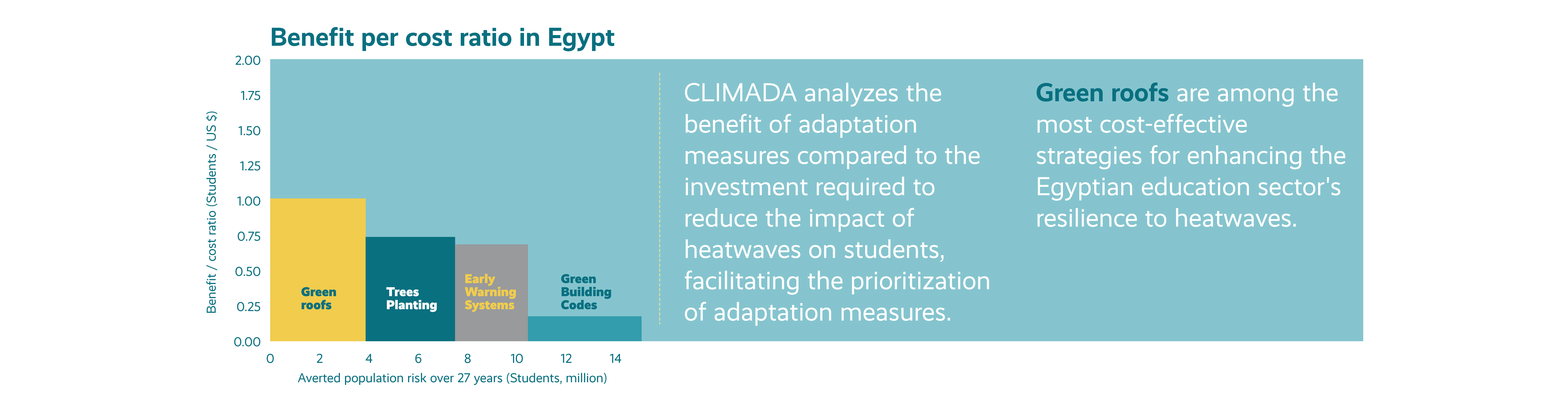

The road to adaptation

To turn from diagnosis to solutions, the Economics of Climate Adaptation approach combines stakeholder engagement, local data and the CLIMADA modelling platform to evaluate risk and compare the costs and benefits of adaptation measures. For heatwave impacts on education, several interventions were analysed, such as green roofs, tree planting, early warning systems and green building codes. Among these, green roofs stand out as one of the most cost-effective options, offering a strong benefit-to-cost ratio. The infographic also visualizes how many students could avoid heat-related disruptions of their education over the next 27 years when well-chosen adaptation measures are in place.

Navigating the future

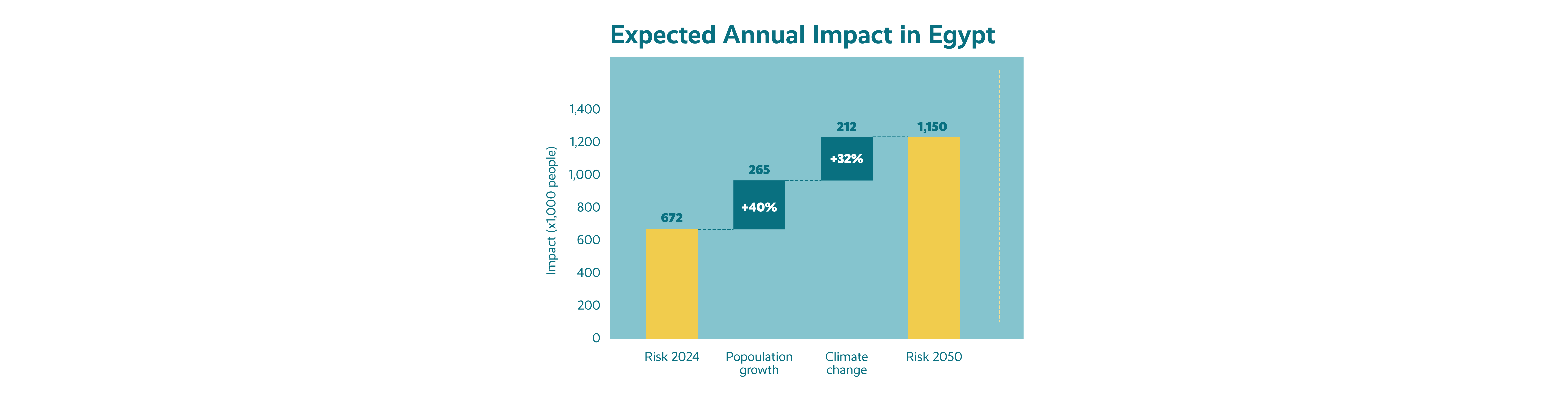

Finally, climate change and population dynamics shape Egypt’s risk landscape going forward. By 2050, population growth alone is expected to drive a 40 per cent increase in expected annual impacts, while climate change adds another 32 per cent. These overlapping pressures underscore why proactive adaptation matters. And this is where the newly developed approach for the ERA project shines: by combining localized risk data with macroeconomic modelling, it helps decision makers identify which adaptation investments can protect people, stabilize consumption and support climate-resilient development.

The complete infographic is available here.