At the 2025 Spring Meetings of the IMF and World Bank, we sought to reframe the climate finance debate. Our message was simple but urgent: the world must move beyond abstract targets and taxonomies to country-specific transformation packages that deliver real-world results.

The stakes are immense. The future of climate finance, foreign aid and global growth hangs in the balance. Rising tariffs, inflationary pressures and political instability are making it harder to sustain climate commitments across both the Global North and Global South. For developing and emerging economies, mounting debt burdens and soaring borrowing costs are squeezing fiscal space and crowding out the investments essential for development and climate resilience.

In this context, more finance alone is not enough. What’s needed is finance that is fit for purpose — rooted in national priorities, designed to manage macroeconomic risks and capable of delivering sustained, system-wide transformation.

We've previously argued that the structure and delivery of climate finance matter as much as its volume. Here, we go further: countries need full-spectrum finance packages that align fiscal and monetary tools within coherent, nationally-led systems. These packages must do more than fund transitions — they must anchor them, making them stable, credible and durable over the long term.

From taxonomy to full capital stack: tools for transformation

To align finance with low-emissions, climate-resilient development — as framed in Article 2.1(c) of the Paris Agreement — we must build capital stacks that are country-owned, systems-oriented and politically feasible.

Delivering a stable energy transformation — including phasing out coal, scaling up renewables and building resilient grids and transport systems — demands upfront capital, long-term planning and macroeconomic stability. These needs are especially acute in middle-income and emerging economies, where emissions are rising fastest and governments are navigating a convergence of climate impacts, debt distress and demographic shifts such as aging populations or youth bulges.

Achieving this requires the coordinated use of monetary tools — like concessional lending, currency hedging and guarantees to reduce risk and attract private capital — alongside fiscal incentives such as subsidies, taxes and levies. Fiscal policy generates demand and cushions risks, while monetary and financial policy helps ensure affordability and macroeconomic stability. When deployed in sync, fiscal and monetary tools can de-risk clean energy and resilience investments, create jobs, boost productivity and minimize the risks of inflation and financial instability. Table 1 outlines how these tools are already being used to support these goals.

Table 1: Monetary goals to support stable energy transformation

| Tool | How it supports stable transformation | Examples |

| Fiscal expansion | Invests in infrastructure, public goods, social safety nets | EU Green Deal, US Inflation Reduction Act |

| Public Investment Banks | Channels concessional and blended capital to energy transition | Development Bank of South Africa (DBSA), Brazilian Development Bank (BDNES) green credit lines |

| Taxes / Pricing | Raises revenue and internalizes costs of energy transition, adverse climate impacts | Sweden, Chile |

| Bonds | Raises long-term finance for energy transition | Nigeria, Indonesia, Colombia |

| Monetary support (credit guidance) | Lowers interest rates for transitioning sectors | China’s PBoC green re-lending |

| Central bank reserve adjustments | Accepts “transition bonds” as collateral | European Central Bank, Bank of Japan experiments |

| Macroprudential regulation | Adjusts capital risk weights for climate exposure | Bangladesh, EU, Brazil pilot rules |

If we want energy and resilience transitions that are both stable and scalable, we must move beyond a menu of disconnected tools toward coherent capital stacks tailored to national contexts. These stacks should align investment, credit, regulation and fiscal policy to drive coordinated action.

Some countries are already moving in this direction. Social protection mechanisms are being used to support just transitions and shield vulnerable communities from the shocks of structural change (e.g., Chile’s Just Transition Strategy for the Energy Sector, Germany’s Coal Commission). Others are leveraging regional and global platforms for joint procurement (the African Union and African Development Bank’s Desert to Power Initiative), harmonizing regulations (the EU’s Green Taxonomy) and integrating markets (cross-border electricity trading schemes in West Africa and South Asia). What’s clear is that successful transitions can’t rely on isolated financial levers; they require systemic alignment.

The good news is that the necessary tools already exist. The challenge lies in coordination: across ministries, financial institutions and time horizons.

Designing large-scale transformation packages raises tough but unavoidable questions: How can countries balance inflation and employment? How can they invest for the future without compromising debt sustainability? How can they ensure transitions are socially just and politically feasible?

Effective capital stacks include diagnostics, sequenced reforms, capital mobilization for high-impact projects and institution-building. When done right, they blend public budgets, development bank financing, concessional instruments and private capital into a long-term strategy for resilience and growth.

These are not merely technical questions — they are political economy choices that require deliberate and inclusive decision-making.

The JET-P Example: South Africa’s Unfinished Transition

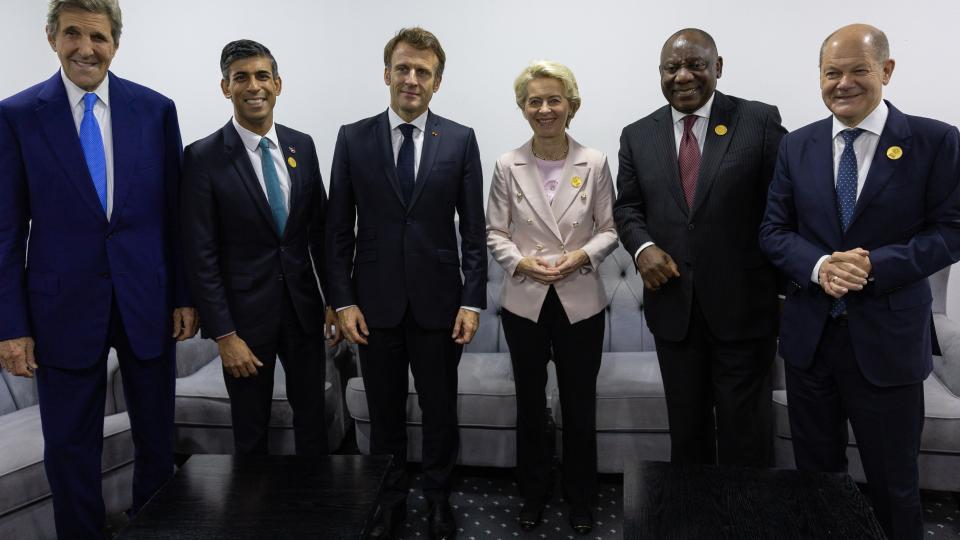

Consider South Africa’s Just Energy Transition Partnership (JET-P). Announced at COP26 as the first of its kind, JET-Ps are plurilateral financing initiatives designed to accelerate the phase-out of fossil fuels in emerging economies, particularly those heavily reliant on coal production and consumption. These partnerships coordinate financial resources and technical assistance from Global North countries to help recipient nations transition to cleaner energy sources while addressing social equity concerns.

The South Africa JET-P, with an $8.5 billion pledge, served as a model for subsequent agreements: Vietnam ($15.5 billion) and Indonesia ($20 billion) in 2022, and Senegal in 2023, which received €2.5 billion. The initiative is primarily funded by France, Germany, the United Kingdom, the United States and the European Union, with additional support from development banks and other international actors. Financing for these partnerships includes a mix of public and private grants, loans and investments.

The ambition is clear, but execution has been uneven. The total cost of South Africa’s transition is estimated at $96 billion, yet only 4 per cent of its $8.5 billion JET-P financing is in grants — reserved for the “just” portion of the transition. The rest is primarily loans, many at near-market rates.

In a country where renewable energy projects face financing costs of 11 or more, this isn’t transformative. It threatens energy security: as coal plants shut down and renewable financing remains too costly, South Africa is considering more oil imports.

This highlights a core paradox: fossil fuels are expensive, but so is the capital needed to move away from them. The stakes extend beyond energy. Coal provides vital export revenue and regional jobs. Without strong fiscal and social buffers, even well-intentioned transitions can spark backlash and instability.

The lesson: if JET-Ps don’t deliver affordable capital and credible social support, they won’t be sustainable. Countries will take notice — and the credibility of climate finance models will be at risk. Table 2 illustrates some of the trade-offs that JET-P countries like South Africa face and the potential tools they can adopt to navigate these trade-offs.

Table 2: Transition trade-offs and relevant tools

| Trade-off | How to Navigate It |

| Debt sustainability vs. climate investment | Use concessional and long-term finance, watch out for short-term debt traps |

| Job creation vs. automation/productivity | Prioritize labour-intensive green sectors (e.g. retrofits, urban transport and green construction, agroecology) |

| Inflation vs. green stimulus | Balance incentives and targeted support (e.g., energy vouchers, nature-positive tax incentives), cautious use of consumer facing tools that affect cost of living (Canada eliminated the consumer-facing component of the carbon tax and retained the business part). |

| Monetary stability vs. credit expansion | Broaden macroeconomic tools such as credit guidance (macroprudential, green taxonomies) to signal stability and reduce pressure on tools like interest rate adjustments. |

Stability isn’t shock-proof — it’s shock-ready

Stability doesn’t mean avoiding shocks. It means having the tools to absorb them.

Transformation packages must build in fiscal and monetary flexibility to handle climate volatility, demographic changes and external disruptions. That includes adaptive social protection, flexible credit lines, labour force planning and countercyclical macroeconomic policies.

Table 3 outlines four broad financing channels that countries are using to manage disruption and build stability. When designed and deployed strategically, each offers unique strengths — but also comes with trade-offs.

Table 3: Financing channels for managing disruption and building stability

| Type | Examples | Strengths | Limitations/Trade-offs |

| Public finance | Budget allocations, development funds | High policy control | Limited fiscal space, opportunity cost |

| Debt instruments | Sovereign green bonds, concessional loans | Predictable, large volumes | Adds to debt, interest rate sensitivity |

| Private capital | Equity, blended finance, PPPs | Innovation, efficiency | Needs de-risking, may exclude poor |

| International climate and biodiversity finance | Global Environment Facility, Green Climate Fund, IMF Resilience & Sustainability Trust | Grants or concessional terms | Complex access, policy conditions |

No single instrument can address the full complexity of energy and resilience transitions. Instead, countries must weave together multiple tools into coherent financing strategies that actively manage trade-offs and reinforce each other. Some are incorporating pause clauses into debt contracts to create fiscal space for recovery after climate shocks; others are partnering with public credit rating agencies or using hedging platforms to reduce investment risks. There are also growing calls for multilateral development banks to support regional food buffer stocks to stabilize prices in vulnerable areas. When deployed in concert, these tools can build the stability and institutional capacity needed to sustain long-term, large-scale transformation.

Why this matters now

The stakes couldn’t be higher. If we fail to deliver on climate finance, we don’t just risk missing temperature targets. We risk fracturing global trust, undermining development goals and fueling political instability.

But the moment is also full of possibility. The geopolitical and macroeconomic shocks of recent years have loosened old assumptions. New institutions, new norms and new coalitions are emerging. There’s space for innovation.

In the next 5–15 years, the challenge is clear: designing stability into the next economy.

That means linking global financial flows to jobs, production and resilience — not just emissions metrics. It means building systems that are climate-aligned, socially grounded and politically durable.

The good news? We know what the tools are. The task now is to use them — together, at scale, and with urgency.

This piece builds on remarks delivered at the 2025 IMF-World Bank Spring Meetings and a recent joint paper on climate finance systems for energy and resilience transitions.

Suggested citation: Michael Franczak, Koko Warner., "Designing climate finance packages that last," UNU-CPR (blog), 2025-05-07, 2025, https://unu.edu/cpr/blog-post/designing-climate-finance-packages-last.