How do we effectively represent and consider the interests of people who are not yet born? This challenge has become increasingly salient since global leaders adopted the United Nations’ Pact for the Future last year and its two annexes: the Global Digital Compact and the Declaration on Future Generations.

While the Declaration’s preamble distinguishes today’s youth from unborn future generations, the fourth Chapter of the Pact (“Youth and Future Generations”) focuses primarily on young people, leaving a gap in how we approach our responsibilities to those who inherit our world; creating fairer futures should not solely rely on the shoulders of younger generations.

The concept of "Future Design" avoids this reliance on younger people and is designed for adults of all ages. Although we haven’t yet solved time travel, Future Design allows us to imagine ourselves in the future - while maintaining our current age and experience – and helps us to think through the consequences of our present-day actions (and inactions). It challenges us to consider how the decisions we make today will impact on the lives of those not yet born.

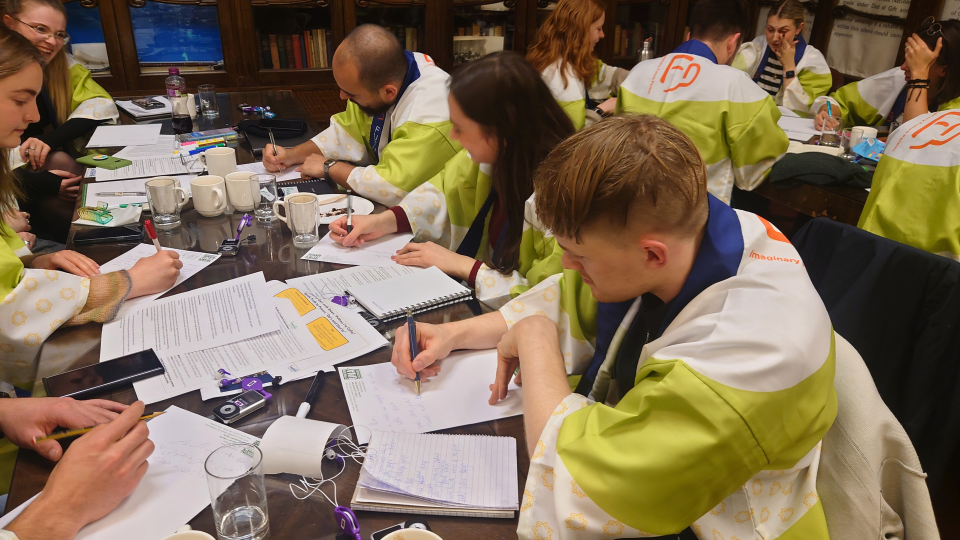

When embarking on a Future Design workshop, we ask people to imagine themselves transported to the year 2050. How would they view the world? What would they want to see? What decisions would they wish their predecessors had made?

Challenging common assumptions about age and future thinking

A common misconception of futures thinking is that young people are more likely to think about the long-term because they have more years ahead of them, while older individuals, aware of their more limited time on earth, tend to focus more on immediate concerns. This assumption has led many to argue that decisions regarding future generations should be largely entrusted to young people, with some even suggesting that older generations might stand in the way of progress.

However, our extensive research and practical experiments with Future Design have revealed that older generations often excel as “imaginary future persons”. When asked to envision life in 2050, young participants typically noted technological advances, from flying cars to high-tech gadgets. Meanwhile, older participants generated more comprehensive and creative visions for society, addressing fundamental social structures, environmental sustainability and human well-being.

This fascinating pattern emerges for several reasons. When young people imagine 2050, they're thinking about a time when they will still be alive. Therefore, their imagination can be limited by personal considerations about their own future lives. Older participants, knowing they are unlikely to be present in that future, can think more freely about what is best for society without personal interests clouding their judgment. This often leads to more radical and innovative proposals for positive change.

What is particularly exciting is how this dynamic can create powerful collaborations. When older participants begin generating creative visions for the future, young participants often build upon these ideas, adding their own insights and perspectives. This collaborative approach mirrors traditional familial structures where three generations – grandparents, parents and children – come together to discuss important matters affecting the family's future.

Comprehensive, long-term decision-making

Future Design consists of three essential processes, each offering unique insights:

- Present Design: The conventional approach to planning, in which a person thinks about the future from their current perspective. While this process includes forecasting to look ahead and backcasting to look backward, its design capacity has inherent limitations and is primarily used to establish a clear understanding of current realities rather than to design the future from present perspectives.

- Past Design: This process goes beyond merely studying history – it involves actively creating "alternative histories". In examining past generations' decisions, Past Design involves imagining alternative visions and paths that could have been taken. Three types of evaluations are considered: grateful appreciation for past generations' choices, critical assessment of what could have been done differently, and recognition of decisions that are no longer relevant. By creating these alternative histories, Past Design develops our capacity to think beyond conventional historical narratives and imagine different possibilities.

- Future Design proper: Participants become imaginary future persons and create what we call "future histories" – detailed pathways from the present to their envisioned future, including the steps and transitions needed to reach these new visions. During this process, participants tend to find more common ground and show greater willingness to compromise than when discussing the same future possibilities from the perspective of their present selves.

Futurability: our capacity for long-term thinking

At the heart of Future Design is the concept of "futurability" – our innate capacity to find joy and fulfillment in sacrificing immediate benefits for the happiness of future generations. It involves developing the ability to derive genuine satisfaction from creating a better world for those who will come after us.

In 2023, the Ministry of Finance of Japan officially established a Future Design group and has conducted numerous Future Design workshops with local governments, corporations and educational institutions, including high schools and universities. Resources and developments on the group are shared on a publicly-accessible portal.

We support extending Future Design to other national and international contexts. During Think 7 (T7) at the 2022 G7 Summit in Elmau, Germany, we proposed in a Policy brief – Future Design: for the survival of Humankind – that world leaders become imaginary future leaders in the year 2050 and use this perspective to inform their discussions on current challenges, including complex issues like international conflicts.

While this proposal was adopted at T7, we have some way to go until its implemented at the G7 level – highlighting the ongoing challenge of incorporating long-term thinking into current political processes.

Creating new histories for a better tomorrow

The appointment of a Special Envoy on Future Generations is now underway at the UN, following commitments made by Member States in the Pact for the Future. While the specifications over who will be considered for the role and what the Envoy’s missions will be are still being defined, the Special Envoy offers an opportunity to intentionally consider future generations in global governance.

Beyond advocating for the needs of future generations, the Envoy should ensure their voices are represented in global decision-making processes. By encouraging a diverse range of participants, not just young people, to engage as “imaginary future persons” during multilateral fora, the Envoy could create spaces for collaborative, intergenerational problem-solving.

Future Design can further support the Envoy in constructing detailed future histories that outline pathways for sustainable development, peacebuilding and global cooperation. In doing so, the Envoy could help ease the collective fear and antipathy towards the uncertainty that are inherent in a non-deterministic world.

Future Design is more than a tool for imagining the future – it’s also a tool for shaping that future. With the Special Envoy soon to be appointed, it could offer critical support as efforts get under way to redefine our relationship with future generations and secure a future worth inheriting.

Suggested citation: Tatsuyoshi Saijo., ""Future Design": an innovative approach to decision-making," UNU-CPR (blog), 2025-03-25, 2025, https://unu.edu/cpr/blog-post/future-design-innovative-approach-decision-making.