Despite extensive media coverage of African migration towards Europe, most Africans tend to migrate within Africa and to other regions of the Global South. In recent years, many have migrated to Latin America, sometimes at great risk.

Our understanding of African migration to Latin America challenges simplistic "push–pull" models of international migration that tend to see migrants as passive individuals “‘pushed”’ to migrate by external factors such as poverty, demographic pressure, conflict, or environmental degradation.

Instead, there is growing recognition that Africans migrate for a variety of reasons – such as family, work, education, and other personal aspirations. The premise that migration is driven exclusively by poverty is also disputed by recent research which highlights the importance of development in African countries: rising incomes, increasing education levels, and infrastructure connections that increase people’s aspirations and their capacity to migrate.

This article seeks to provide a more nuanced analysis of African migration to Latin America. It reviews several studies that have discussed the determinants, context, and challenges involved in the arrival of African migrants in a historically migrant-sending region. We then use refugee and detention data to map the trends of African migration flows to and through Latin America, and subsequently highlight four key characteristics of African migration to Latin America: its rapid increase, its relatively new and pioneering character, the wide cultural and geographical distances travelled, as well as the diversity of the characteristics, aspirations, and capabilities of those who move.

Latin America: A New Destination for African Migrants

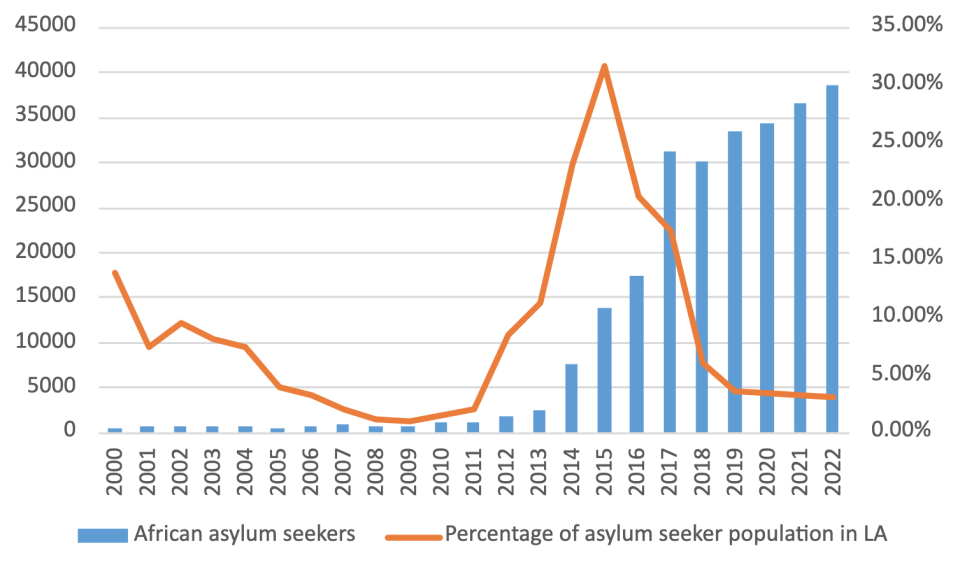

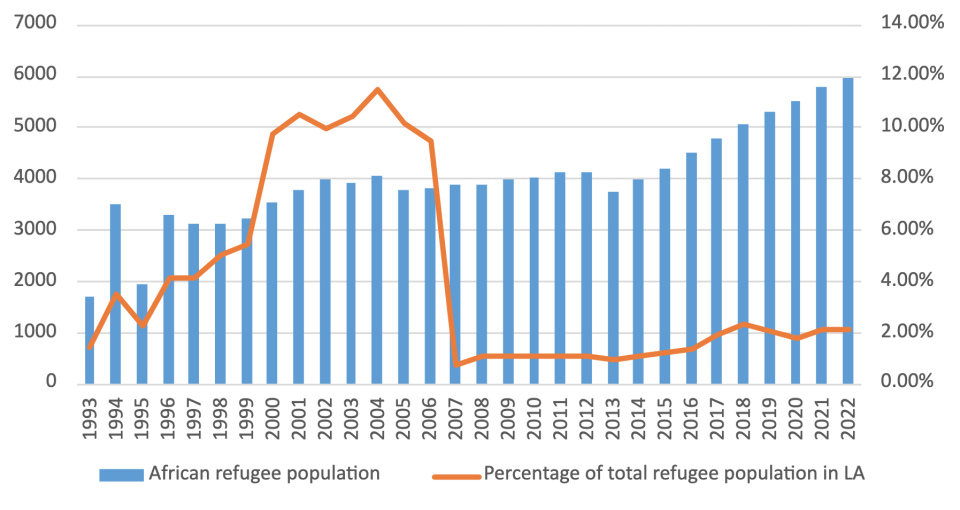

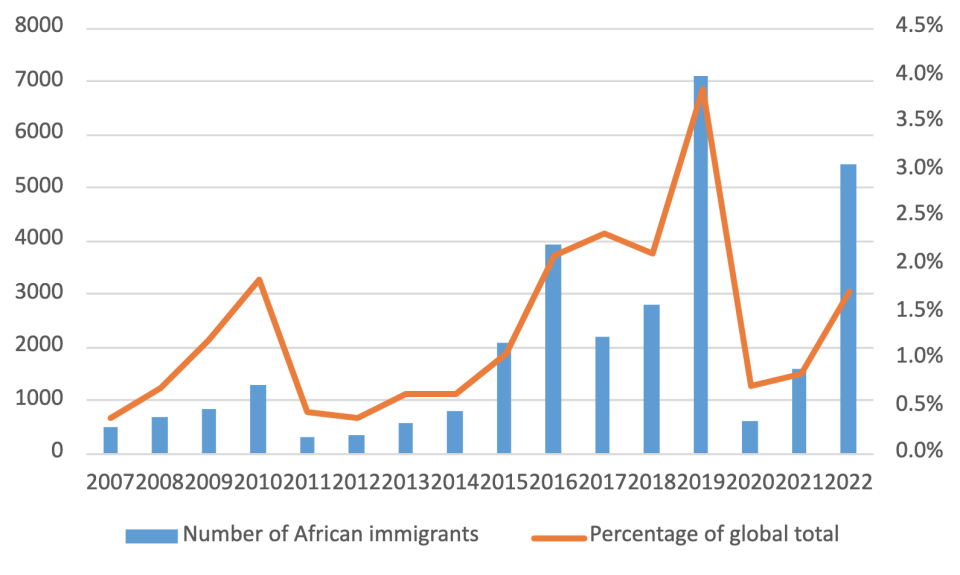

Although data is limited, it’s possible to map trends in African migration flows to Latin America using UNHCR data on asylum seekers and refugees and data compiled by Mexican border authorities on the number of detained African migrants. While both sets of indicators have limitations, they both suggest a significant increase in African immigration to Latin America.

The main receiving countries of asylum seekers and refugees are Argentina, Brazil, and Mexico. According to UNHCR figures, the number of asylum seekers originating from Africa in Latin America increased from 1,849 to more than 38,000 between 2012 and 2022; the number of asylum seekers has increased by 8,000 per cent since 2020; and in 2015, African asylum seekers accounted for more than 30 per cent of the region’s pending asylum applications. These changes sparked a political backlash across the region – which only dissipated when attention shifted to focus on the 6 million people displaced by the crisis in Venezuela (even though the numbers of pending asylum applications from Africans were at an all-time high).

Moreover, UNHCR data show that while the number of asylum seekers has increased, this has not translated into an equivalent increase in the total number of applicants recognized as refugees. Rather, the number of African refugees in Latin America has remained extremely low.

As for the number of African migrants detained in Mexico, these increased ninefold between 2014 and 2019, and despite an abrupt drop in detentions during the COVID-19 pandemic the number of detainees had increased again by 2022, suggesting an increase in African migration to the United States via Mexico.

Why is African Migration to Latin America on the Rise?

Among the factors leading to an increase in African migration to Latin America is the liberalization of immigration policies in Latin America - including the relaxation of entry visa regimes - and relative economic stability in the aftermath of the 2008 financial crisis. A striking example of policy liberalization in Latin America was Ecuador’s “open door” policy that eliminated the need for entry visas for all nationalities in 2008 (which has now been partially reversed).

Despite migration liberalization policies, however, Latin American countries have not been adequately equipped to integrate African immigrants, which has historically been considered a group in transit. In this sense, there have been significant difficulties in the regularization of African migrants and the adequate provision of humanitarian protection and services. As a result, there is an "implementation gap" in migration policies due to legislative loopholes and bureaucratic barriers that create difficulties for migrants seeking to regularize their status. These problems arise in the context of a considerable backlog of asylum claims since both migrants and refugees seek asylum to regularize their stay.

Intersectional forms of discrimination, the marginalization and mistreatment of a person based on intersecting identify markers such as race/ethnicity, gender, nationality, language, or immigration status, and the securitization of migration across the region, have also been barriers to socioeconomic integration. In the case of intersectional discrimination, there are linguistic and information barriers, while structural racism and other forms of discrimination also remain widespread. Many African migrants have a lack of information about their options for remaining legally in transit countries, and in extreme cases, have reportedly been detained and harassed by immigration authorities.

What Lessons Can We Draw from African Migration to Latin America?

First, African migration to Latin America reminds us of the need to recognize the complexity of inter-regional and cross-continental South–South migration and to acknowledge the varying degrees of aspirations and capabilities of migrants and refugees as agents of their personal life projects. This provides a counterweight to widespread prejudicial views or partial approaches to African migration more generally.

Secondly, our research makes clear the urgent need for better data to develop and adapt immigration and integration policies to address the needs and capabilities of new arrivals. The availability and processing of data in Latin America has tended to focus on Venezuelan displacement in recent years, overlooking the specific characteristics and needs of other migrant flows. International organizations such as IOM and UNHCR, as well as State entities (including migration departments and refugee commissions), should therefore include all immigrant groups in their data collection efforts and develop a regional interoperable information platform.

Finally, national and local governments, international organizations, civil society, and academia, must jointly contribute to designing and implementing forms of migration governance that guarantee the human rights of all migrants and refugees, particularly the most vulnerable.

Two compelling examples can be found in Peru: the Intersectional Working Group for Migration Management, a mutistakeholder commission under the Foreign Ministry, responsible for coordinating comprehensive migration policies, and the efforts of the Migration Chair of the Universidad del Pacifico, funded by the International Development Research Centre, which enables a more open dialogue in often restricted political spaces.

The persistence of everyday and institutional racism against migrants of African origin requires Latin American societies to rethink and challenge deeply entrenched socioracial hierarchies in the region that are often sugar-coated by colourblind public discourses. Cultural mindsets may be difficult to change, but evidence-based interventions can challenge perceptions. At the very least, African immigration offers an opportunity to initiate public debates about structural discrimination.

Suggested citation: Luisa Feline Freier, Leon Lucar Oba., "A Brighter Future Across the Atlantic?," UNU-CPR (blog), 2024-04-17, 2024, https://unu.edu/cpr/blog-post/brighter-future-across-atlantic.