The United Nations has increasingly come to recognize that cities possess the potential to play a transformative role in promoting sustainable development. Evidence of this is most visible in the agreement within the UN Open Working Group on Sustainable Development Goals to establish a stand-alone goal on cities (Goal 11), as well as in the decision of the United Nations Secretary-General to appoint Michael Bloomberg as the Secretary General’s Special Envoy for Cities and Climate Change.

Part of this realization builds on increased recognition of the fact that the world’s economic activity and growth are heavily concentrated in cities. According to the McKinsey Global Institute, cities generate more than 80 percent of global GDP today. While this wealth has been disproportionately concentrated in the developed world’s largest cities, this reality is about to shift radically, with nearly 40 percent of global growth expected to come from cities in emerging markets by 2025.

While this trend bodes well for cities such as Bursa, Istanbul, Izmir, Kunming, Kuala Lumpur, Hangzhou, and Delhi, which are all in the top 20 fastest-growing metropolitan economies in the world, what does it mean for cities in fragile and conflict-affected states? In other words, what are the implications for cities mired by unanticipated disasters and violent conflict? Can we expect to see fragile cities driving national and even regional development across conflict and disaster-prone countries in Sub-Saharan Africa, Southeast Asia, and the Middle East and North Africa? What do the prospects look like if we remove the dominant impact of cities in China, India, Brazil and Turkey from these projections for growth?

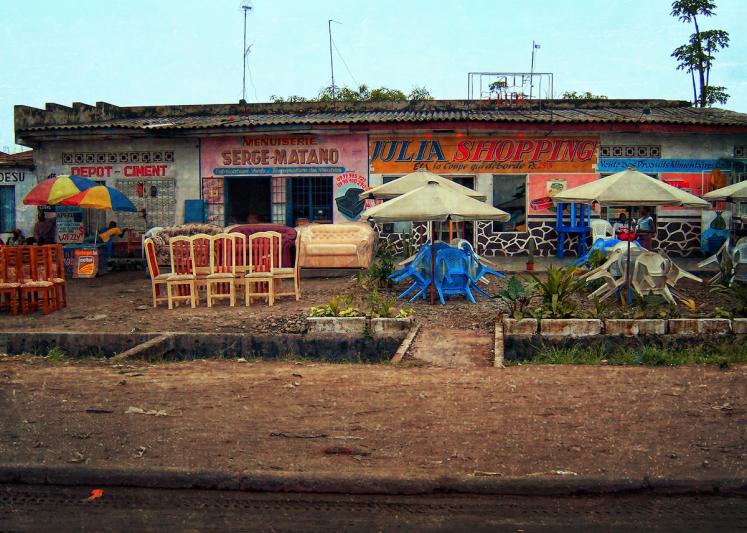

According to economists, the answer is that cities will drive development in fragile contexts as well. A variety of international consulting firms unanimously support the idea that cities in these regions will dominate economic growth. In fact, according to the McKinsey Global Institute, 70 percent of total GDP growth in Sub-Saharan Africa between 2010-25 will be generated by cities in the region. In the Middle East and North Africa this figure will rise to 80 percent and in Southeast Asia, cities will constitute 66 percent of regional economic growth. One of the fastest-growing cities in Sub-Saharan Africa is Khartoum (Sudan), which is expected to more than double its GDP within the next 10 years. In Southeast Asia, Yangon (Myanmar) is projected to grow even more dramatically from its current GDP of USD $8 billion to $24 billion by 2025. According to A.T. Kearney’s Global Cities Index, Kinshasa and Karachi, both of which are considered fragile, are ranked within the top 80 global cities worldwide.

Table 1: Projected Growth in GDPs of Select Cities in Fragile States

(based on data from McKinsey Global Institute)

|

City

|

Total GDP

|

Population

|

|

Baghdad (Iraq) |

2010: US $17 billion 2025: US $46 billion |

2010: 5 million 2025: 9 million |

|

Khartoum (Sudan) |

2010: US $43 billion 2025: US $93 billion |

2010: 9 million 2025: 14 million |

|

Karachi (Pakistan) |

2010: US $28 billion 2025: US $67 billion |

2010: 13.5 million 2025: 20.2 million |

|

Kinshasa (Democratic Republic of the Congo) |

2010: US $17 billion 2025: US $48 billion |

2010: 8.8 million 2025: 15 million |

|

Yangon (Myanmar) |

2010: US $8 billion 2025: US $24 billion |

2010: 4.3 million 2025: 6.3 million |

These projections underpin the notion that urbanization can be a potential pathway out of poverty for some of the most fragile and conflict-affected countries. This conforms to the historic pattern of city-driven economic growth. In fact, evidence shows that no country has ever achieved sustainable economic growth without urbanizing. Cities have historically been where the most employment opportunities are located. They are often the engines of creativity and wealth generation and have served as important hubs for technology and transportation. Cities are where government and commerce are centred and have been associated with higher levels of literacy, better health, enhanced political participation, and greater access to social services. Furthermore, cities have often served as sanctuaries for displaced populations in times of war.

While opportunities do exist to harness the transformative potential of cities in fragile and conflict-affected contexts, rapid urbanization threatens to derail this possibility. Over the past forty years, the urban population in lower-income and fragile countries has increased by an astonishing 326 percent. This growth has been unplanned and as a result, the majority of urban residents in fragile and conflict-affected countries live in precarious informal settlements that are characterized by poor housing, a lack of access to adequate sanitation and public services, rampant crime and violence, and significant pollution. According to UN-Habitat, over 75 percent of urban populations living in countries emerging from conflict live in slums. This amounts to approximately 1 billion people. This fact has contributed to the finding that the number of people affected by disasters in fragile and conflict-affected states is disproportionately high.

Cities are also responsible for some 70 percent of global greenhouse gas emissions. Homicide also appears to be largely an urban phenomenon. According to the UNODC’s Global Homicide Report, homicides in the national capital regions of countries such as Haiti, Liberia and Sierra Leone significantly outstrip national averages. In fact, in 2012 the Haitian capital of Port au Prince accounted for some 75 percent of national homicides. Additionally, extreme inequality is also a reality in many of these cities. The African Development Bank notes that inequality in African cities is the second highest in the world after Latin America. Given these realities, the prospects for growth in fragile contexts put forward by the aforementioned reports seem increasingly uncertain.

The extent to which cities in fragile and conflict-affected contexts can be catalysts for sustainable development will depend on two key factors: (1) the degree of exposure and susceptibility to risks that can derail growth (major disasters, extreme violence, disease epidemics, political instability, and extreme poverty), combined with (2) the degree to which their governments, institutions, and residents develop coping and adaptive capacities to mitigate and reduce these risks. While natural hazards are impossible to predict and violent conflict difficult to prevent, as the World Risk Report 2014 underscored, the question of whether individual countries and cities are able to harness urban opportunities largely depends on the development and implementation of effective risk governance strategies and capacities.

Public authorities and residents of fragile cities will need to develop ways to better absorb disruption and to operate under a wide variety of conditions that may arise as a result of exposure to disaster and violence. This means that fragile cities have to develop the ability to anticipate and respond to risks. They will also have to foster and harness protective factors – characteristics that strengthen the ability of individuals, communities, and states to confront stresses without resorting to violence – that already exist within their societies. These factors include reducing the exposure of children to violence and promoting their interaction with positive family role models; supporting proactive community associations and engaged schools; promoting links between neighbouring communities; as well as productive employment opportunities, among others.

Resilience in these cities cannot be imposed from above. Instead it needs to be, and often is, embedded in the relationships that mediate people’s everyday lives. In many cases, fragile cities have already developed some of these capacities through informal networks. In fact, research has shown that some of the most resilient people and communities are those in places that have experienced deep challenges (i.e. fragile cities and countries). These capacities have developed as a result of having to overcome repeated disruptions and challenges to the point where a culture of resilience has emerged through informal networks that are rooted in trust.

In support of such adaptive capacity, new technologies and solutions are also emerging that may prove useful in fragile cities. These include open data initiatives that can help cities monitor and evaluate interventions; the development of critical infrastructure (electrical grids, water, telecommunication, banking and finance systems) that has an embedded capacity to adapt and reconfigure in times of disaster in order to prevent failures in one part of the system from cascading through the larger whole; as well as a series of predictive modelling as a result of scalable “smart” innovations such as the US Geological Survey’s Twitter Earthquake Detector or Oracle’s socially enabled policing. The role that Cloud Computing can play in supporting a dynamic Common Crisis Information Management System for decision makers and communities in times of crisis should also not be underestimated. Old fashioned solutions such as land use planning, insurance schemes, education, and community mobilization are also important.

However, the reality is that current urban development patterns, particularly in fragile and conflict-affected countries are not sustainable. If left as is, it is difficult to imagine how cities in fragile and conflict affected countries can help drive development in a sustainable way. For this to happen, there is an urgent need for local, regional and international stakeholders to tackle the challenge of translating the promise of resilience into practical gains on the ground by developing and supporting realistic (preferably organic) solutions that are adapted to deal with recurrent risks in fragile cities.

Suggested citation: Dr John de Boer., "Can Cities Drive Sustainable Development in Fragile and Conflict-Affected States?," UNU-CPR (blog), 2015-03-25, https://unu.edu/cpr/blog-post/can-cities-drive-sustainable-development-fragile-and-conflict-affected-states.