Oil palm is an exceptionally profitable crop used in a wide array of consumer products and as a biofuel. Since the 1960s, production has grown over 500 per cent, in part through promotion by development actors. Today, 17 million people’s livelihoods depend on the industry. Palm oil promotes growth and poverty reduction at the national level, but has variable impacts at the community level, depending on the prior institutional setting and the commercial structure of production.

In Indonesia and Malaysia, most production occurs on private plantation estates, or on the land of smallholder ‘outgrowers’ operating under a long-term purchasing deals. Malaysia’s industry has been shaped by close state-industry cooperation. 70 per cent of agricultural land is now oil palm. Malaysian firms have sought to reproduce close cooperation with the state in Indonesia. Palm oil now contributes around 12 per cent of Malaysian export earnings. But the growth of the industry has also brought local corruption, with district governors (bupatis) competing for access to foreign capital by facilitating access to low-cost land and labour. In Nigeria, we see more cooperative production and wild harvest from traditional, pre-industrial groves. Plantation production has only found success with the recent arrival of firms from South East Asia.

Modern slavery risks vary across these contexts. Production quotas, wage penalties, isolation, debt and coercion are often used to force work. But vulnerability seems to vary on two main dimensions: political agency (i.e. reduced protection by the state) and control of land. In Indonesia, forced and child labour risks arise amongst the casual labour force on plantations and smallholdings, especially amongst indigenous people and internal migrants. In Malaysia, risks are connected in particular to the management of foreign migrant workers, who are often in debt bondage connected to recruitment fees. Women are at heightened risk, as are the ‘stateless’ children born to foreign migrant workers in Malaysia. In Nigeria, risks relate to adverse incorporation of smallholders into export-oriented plantations.

Most sustainability efforts have focused on the sector’s environmental impact, including carbon emissions, biodiversity loss, and harmful haze – which is thought to have caused 100,000 deaths in South East Asia during one episode in 2015. The turn to labour practices has been more recent, and efforts in this area largely adopt a “techno-managerial” approach, framing issues in terms of workforce management without addressing underlying questions such as access to and control of land, labour migration governance, corruption and structural inequality. They focus on the physical production of palm oil without addressing its social production, and the ways in which state policies shape the interaction of land, labour and capital flows to generate rents from the restriction and control of vulnerable people’s economic agency.

Sustainability efforts have become geopolitical questions as different states ally with different actors in the value chain. The Roundtable on Sustainable Palm Oil (RSPO), a multi-stakeholder certification scheme, covers around 19 per cent of global supply. Initial cooperation from Indonesia and Malaysia morphed into resistance as sector leaders in each country came to perceive the RSPO as a threat to their autonomy. Both countries characterized the RSPO’s prioritization of environmental concerns as a threat to their sovereign choices to prioritize other aspects of sustainable development, such as economic growth, poverty reduction and people’s livelihoods. Both countries created national certification schemes, which they presented as lower-cost options better tailored to local commercial realities and development priorities. This politicized dynamic has deepened since the EU removed palm oil from its list of approved biofuels (on deforestation grounds), and the US moved to hold some palm oil products at its border (over forced labour concerns).

In recent years, there have been attempts to foster convergence across the palm oil ‘regime complex’ around shared public policy goals, particularly through the RSPO certifying entire jurisdictions. This may offer opportunities for addressing sustainability governance and economic agency in a more direct way, but also raises questions about voice and representation. Development actors have an important role to play in promoting coherence to maximize worker and smallholder economic agency. The World Bank, IFC, UNDP and UN Environment Programme are all promoting palm oil smallholding as a path to sustainable development. Private capital markets and development finance entities may have a role to play to address barriers to smallholder financing (opaque land tenure, exposure to local political risk, lack of access to credit histories). More work is needed to address the state policies that reproduce a vulnerable labour force available for the industry’s exploitation, through standardization of contracts, promotion of collective bargaining and other agency-enhancing measures.

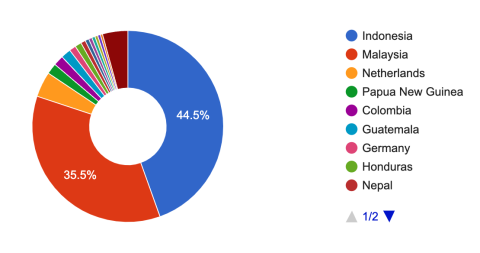

Top 15 palm oil exporting countries in 2019, USD billions (Figure 28)

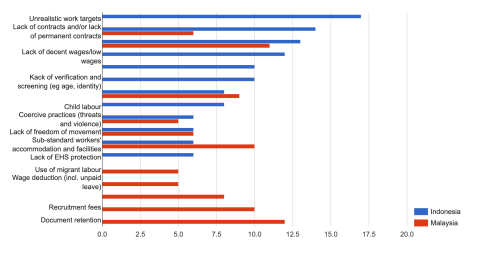

Palm oil labour management concerns of stakeholders – Indonesia & Malaysia (Figure 29)

Suggested citation: "Palm Oil," United Nations University, UNU-CPR, 2024-05-01, https://unu.edu/cpr/article/palm-oil.