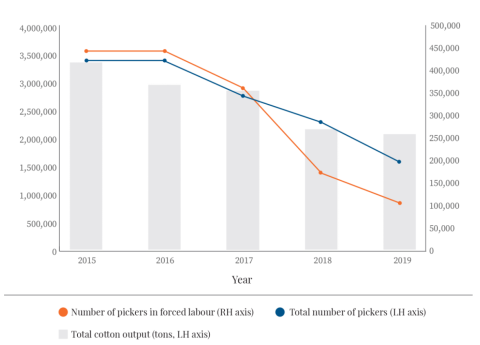

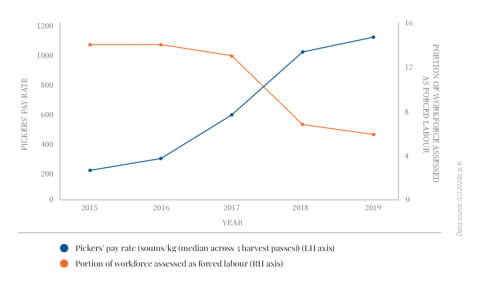

From 1992 to 2017 around one fifth of the adult population of Uzbekistan experienced forced labour in the cotton harvest each year. Yet the number of people in forced labour fell from 448,000 in 2014 to 102,000 in 2019 (ILO). This effort to disrupt systematic forced labour in Uzbekistan is arguably the most effective large-scale prevention campaign in recent times.

Forced labour in the Uzbek cotton harvest was a legacy of the Soviet command economy. Farmers were forced to grow cotton and sell it to the state at suppressed prices, while around two to three million people were mobilized each summer in a two to eight week corvée to pick cotton, unless they could buy or bribe their way out. Multiple institutions of society participated in this mobilization: local mahalla neighbourhood committees, universities and colleges, hospitals and clinics, public and private sector employers, and through mosques, all backed up by the state’s security apparatus. A range of coercive techniques was used, from violence and intimidation, to prosecution, quotas, taxes and social pressure. That coercive pressure was dressed up through use of social norms such as patriotism, piousness and solidarity. The system appears to have siphoned off billions of USD in rents to ruling elites, some of it moved offshore. Forced labour in the cotton industry was made possible by, and helped reproduce, a system of authoritarian rule.

Since President Mirziyoyev took power in 2016, however, Uzbekistan’s approach has changed dramatically. Four additional factors combined with Uzbek government leadership to produce rapid change:

- Sustained disruption pressure from a concerted international boycott campaign. This steadily raised the costs of systematic forced labour for the Uzbek elite;

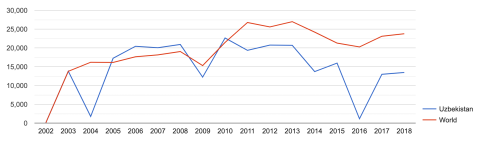

- Falling rents from cotton due to the negative development impacts of forced labour. Cotton accounted for 90 per cent of Uzbekistan’s exports in 1992. By 2016 it was just 3.4 per cent. The indirect costs of the forced labour system have been estimated at USD 211 to 291 million per year, and forced labour contributed to inflation, hurt human capital formation (by disrupting education), retarded innovation, and led to environmentally harmful land management;

- Effective engagement by the World Bank, ILO and international donors (including France, Germany, Japan, Switzerland, the UK and US; the EU, OSCE and other UN entities; and the EBRD); and

- Brave pressure from civil society and human rights defenders, which led to growing emphasis in government and international interventions on empowerment of Uzbek people and workers.

The result has been sustained reform by Uzbek authorities, who have withdrawn state support for forced labour, increased punishment and, in May 2020, abolished the centralized production system for cotton altogether. The case provides insights into the dynamics of engagement that lead to such rapid and large-scale reform. These include:

- The importance of effective strategic coordination between international actors. A ‘good cop bad cop’ dynamic between boycotters and engagers proved effective;

- The persistence of social institutions sustaining forced labour even after formal government support is withdrawn. Transformation efforts need to focus on both informal and formal institutions; and

- The need to consider remedy. Stolen assets recovery and transitional justice tools may be relevant.

ILO estimates of Uzbek cotton production and labour force between 2015-2019 (Figure 31)

Indexed growth in cotton exports – Uzbekistan v. world, 2002-2018 (Figure 32)

ILO estimates of Uzbek cotton industry forced labour vs. pay rate: 2015-2019 (Figure 33)

Suggested citation: "Cotton," United Nations University, UNU-CPR, 2024-05-01, https://unu.edu/cpr/article/cotton-0.