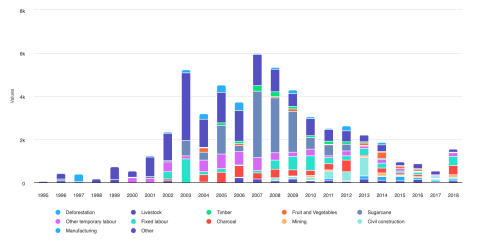

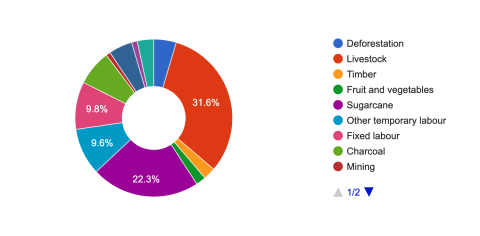

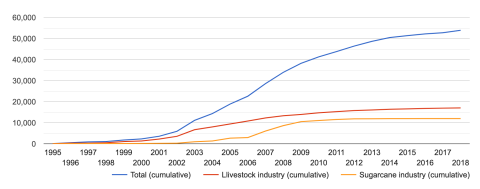

Over the last 25 years Brazil has developed the most sustained and sophisticated domestic anti-slavery disruption effort in the world. This has been supported by civil society, the ILO, US, Norway and – to some extent – Brazilian business. It has rescued over 55,000 people from conditions of slavery. Around one third of those people worked in the cattle industry.

Activities from which enslaved people were rescued in Brazil, 1995-2018

Slavery in Brazil’s cattle industry is a product of several interacting factors. First, an institutional environment encouraging meat production in areas and supply chains where the state’s enforcement power is weak, including the Legal Amazon and Cerrado. Second, a pool of marginalized, poor rural labourers (peões) susceptible to discrimination and exploitation. It is not the poorest of the poor, but the working, landless poor, with limited access to education, capital and finance that appear most susceptible to enslavement in the Brazilian cattle industry. Third, use of coercion and fraud by recruiters (gatos), contractors and producers to compete on labour costs, while harnessing traditional norms of social dependency and obligation and market norms of financial debt, to control workers’ economic agency. Supply chain traceability is limited, and producers blame recruiters and foremen for poor labour practices. Many producers also enjoy effective impunity because of the isolation of their ranches, deliberate corruption of police and government officials, and intimidation of workers.

Brazil’s disruption effort has evolved over time, through a series of collaborations between government, civil society and business, notably the Commission for the Eradication of Slave Labour (Comissão Nacional de Erradicação do Trabalho Escravo – CONATRAE) and a successor National Pact. Government has developed a series of powerful tools for disrupting exploiter strategies, including mobile labour inspections and courts, and the famous ‘dirty list’ (lista suja) of companies found to have engaged in slavery or employed workers in slavery-like conditions. The lista suja became an important reference for both buyers and public and private lenders to use in screening out businesses that rely on slavery.

Yet disruption efforts have lost momentum in recent years, as actors with interests in the cattle and other affected industries have counter-mobilized through judicial, political and extra-judicial channels. The National Champions Policy (2008-2013) saw Brazil’s national development bank, the Banco Nacional de Desenvolvimento Econômico e Social (BNDES) and foreign lenders provide billions of dollars of concessional financing to and take equity positions in several cattle-industry firms, allowing them to move up the global value chain. By 2013 one of these companies, JBS, had become the largest meat-processing firm in the world. But it has also been linked to bribery scandals, and in 2014 was Brazil’s largest political donor. Politicians with close ties to the agribusiness sector have pushed back against the anti-slavery agenda.

As government steps back, civil society is encouraging private sector leadership to change supply chain management practices, including through big-data solutions. This may give Brazil an important first-mover advantage in developing data-driven supply chain solutions for managing modern slavery risks.

Sectoral breakdown of those rescued from slavery in Brazil 1995-2018 (Figure 24)

Rescues from selected industries in Brazil, cumulative, 1995-2018 (Figure 25)

Suggested citation: "Cattle," United Nations University, UNU-CPR, 2024-05-01, https://unu.edu/cpr/article/cattle.