This contribution was published as part of the UNRISD Think Piece Series Beyond Copenhagen: Rethinking Social Development for the 21st Century, which supports UNRISD’s efforts to shape the agenda of the Summit convened in Qatar in November 2025. This series brings together experts from academia, advocacy and policy practice to critically explore the achievements and shortcomings in the implementation of the 1995 Copenhagen Declaration and Programme of Action, current social development challenges, and transformative policies and drivers of positive change. We examine not only the policies and institutional reforms needed for social development and just transitions but also the roles of key actors in advancing social, economic and climate justice. The insights gained from this series have informed the negotiation process of the Political Declaration of the Second World Summit for Social Development, as well as its implementation, monitoring and follow-up.

Tax systems are among the most powerful, yet underappreciated, structural determinants of health. While much of the limited global health literature on taxes focuses on so-called ‘sin taxes’ aimed at curbing consumption of harmful products, the broader role of tax policy for health outcomes is often overlooked. From income redistribution to promoting better governance, a well-designed tax system can address the social and economic drivers of health inequalities. Tax policy, particularly in low- and middle-income countries (L&MIC), plays a crucial role in fostering universal health coverage (UHC), reducing preventable mortality, and advancing social justice. In light of ongoing revenue losses due to tax avoidance and abuse, and the constraints imposed by international financial policies, it’s time for global health leaders to adopt a more holistic approach to tax policy and systems.

Taxes and Global Health

The field of global public health is broad. It includes a focus on diseases and illnesses, but it also requires a consideration of the social, economic, and political determinants of health. Indeed, as noted by the WHO’s Commission on Social Determinants of Health, the unequal distribution of health-damaging experiences “is not in any sense a ‘natural’ phenomenon but is the result of a toxic combination of poor social policies and programs, unfair economic arrangements, and bad politics”. This quote may be viewed as an echo of Rudolf Virchow’s much earlier but equally famous assertion that “politics is nothing more than medicine on a larger scale” and that “should medicine ever fulfill its great ends, it must enter into the larger political and social life”.

Despite this, mainstream public health and the prevailing narratives of global health tend to emphasize biomedical interventions and technological solutions. These technocratic and donor-driven approaches that favour discrete interventions over systemic transformation marginalize considerations of structural determinants that shape health outcomes.

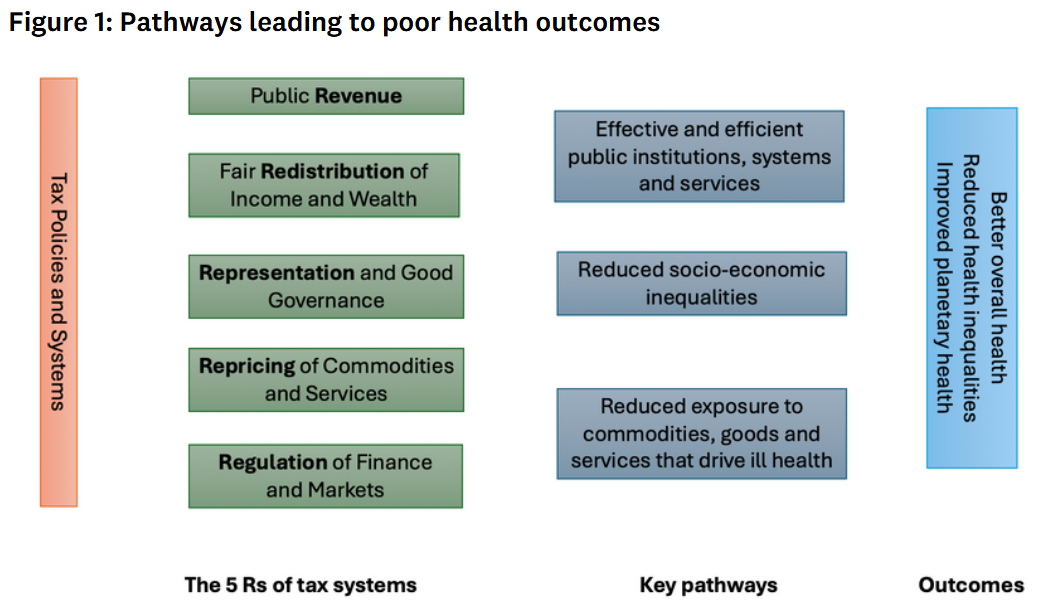

Nowhere is this better illustrated than in the way the global health discipline treats the issue of taxes. Search any of the leading global health journals for significant references to tax policy, and you will find only a few articles. Moreover, what references are made about tax policy will mostly be limited to health taxes: taxes attached to the sale of harmful commodities such as tobacco, alcohol, and sugar sweetened beverages. Such taxes are typically framed as both a potential source of public health revenue and a behavioural intervention designed to reduce the consumption of unhealthy products. The role of taxes, however, is far more extensive than this. In fact, tax policies have five functions which all contribute positively to health.

The five functions of taxes

A briefing paper published by UNU-IIGH, UNRISD, and Tax Justice Network argues that tax systems may be the most important foundation of good global health, making their neglect a perplexing and troubling state of affairs.

In addition to using taxes to increase the price of harmful commodities (Repricing) and to generate government income to finance healthcare (Revenue), there are three other functions of tax that can improve health. The first of these is Redistribution. Progressive tax systems can reduce socioeconomic disparities which in itself can improve the overall level of population health through various social and biological pathways.

Another function is Regulation. Taxes can be used to shape commercial behaviour and market conditions in ways that promote health. For example, foreign currency transaction taxes can be used to discourage short-term, high-frequency currency speculation which can destabilize national economies.

Finally, well-designed tax systems can contribute to better governance (Representation). Research shows that when people pay taxes, they gain legitimacy to demand accountability from governments, while governments are incentivized to deliver public goods effectively.

These five functions of tax, often referred to as the five Rs, work together to improve health and reduce health inequalities through three key pathways as shown in the figure below. These pathways demonstrate how taxes can strengthen public health services and create more effective and equitable universal systems, as opposed to segmented, privatized and commercialized health systems that are more costly, inequitable and injurious.

Pathways leading to better health outcomes through tax

Failing tax policies and systems

While L&MICs with effective and progressive domestic tax policies can achieve universal health care and lower preventable mortality, their capacity to do so is limited by deeply embedded structural inequalities. L&MICs in particular face significant revenue losses due to tax avoidance and evasion, exacerbated by unfair global tax rules, weak enforcement capacity, and the political influence of transnational corporations. The combined global public revenue loss for 2024 is estimated at USD 492 billion, of which USD 347 billion was due to corporate tax abuse and USD 145 billion due to the offshoring of wealth in tax havens by individuals. Lower-income countries lost about 36 percent of their public health budgets as a result. These losses severely curtail states’ ability to fulfil basic economic and social rights, including the right to health.

If the almost USD 500 billion annually lost to corporate tax abuse were recovered, governments could increase access to basic sanitation for 22 million people and access to safe drinking water for 14 million more, benefits which directly reduce disease burden and child mortality. Alternatively, the same volume of recovered revenue could support hundreds of thousands of children through improved education and health infrastructure, investments that have well-established payoffs in early childhood development, nutritional status, and long-term socioeconomic stability.

L&MICs are also constrained by the so-called ‘tax consensus’: the prevailing set of policy prescriptions promoted by the World Bank and IMF. This consensus is characterized by three features: a prioritization of economic neutrality through reduced direct taxation, a preference for achieving redistribution via progressive spending rather than progressive taxation, and the adoption of low public revenue targets. These measures have collectively constrained the fiscal space available for social spending, shifted tax burdens onto lower-income populations, and weakened the regulatory and representative functions of tax in many L&MICs. But these constraints are often neglected by the global health community.

Ending the neglect of tax policy and systems

It is surprising that tax policies and systems, and the actors who influence them, do not receive the due attention in the global health discourse they deserve. The global health community is thus not only missing an opportunity to address the root causes of health inequalities but also perpetuating a fragmented view of health. Foregrounding taxation as a structural determinant of health is not simply an academic exercise, it is a call for a more politically and ethically engaged global health practice. In November 2025, governments and civil society actors will gather at the second World Summit for Social Development. This is an example of a forum where the global health community must add their voices in advocating for fiscal and tax justice as a precondition for effective and equitable health systems.

Taxes are not just instruments of repricing unhealthy products, they are a transformative social superpower for shaping societies in ways that support health, equity, and democratic governance. Failure to use this social superpower risks rendering global health as an ambulance service, or worse, as a tacit legitimizer of rampant tax abuse and unjust political and economic systems.

This piece was originally published on the United Nations Research Institute for Social Development (UNRISD) website. The original version is available at: https://www.unrisd.org/en/library/blog-posts/perplexing-and-troubling-the-neglect-of-tax-policy-in-global-public-health-discourse. The piece draws on key insights from the publication 'Tax systems and policy: Crucial for good health and good governance' by Cobham A, Hujo K, O’Hare B, Nelson L, and McCoy D. 2025. It reflects the views of the author(s) and does not necessarily represent those of the United Nations Research Institute for Social Development (UNRISD).

Suggested citation: Maya Li Preti, David McCoy. "Perplexing and Troubling: The Neglect of Tax Policy in Global Public Health Discourse," United Nations University, UNU-IIGH, 2025-12-17, https://unu.edu/iigh/article/perplexing-and-troubling-neglect-tax-policy-global-public-health-discourse.