We often discuss paradigm shifts as distinct, singular events that abruptly redefine our world. Yet, we now exist within a continuous spectrum of shifting paradigms. Our current reality is one of constant, complex transitions driven by layered forces: technological disruption, environmental urgency, pervasive global inequality and the fundamental reconfiguration of knowledge itself.

The term ‘paradigm shift’, coined by philosopher Thomas Kuhn, initially referred to revolutionary changes in scientific practice. Kuhn observed that when enough anomalies accumulate within an old model, a crisis emerges, necessitating a radically new framework — one shaped not just by logic, but by social and subjective pressures.

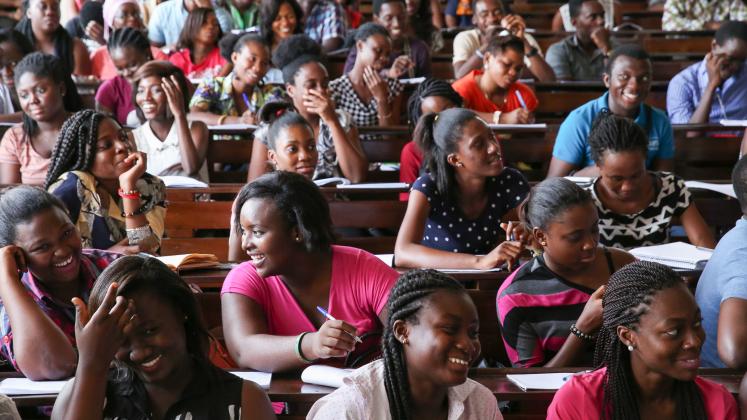

This insight resonates deeply beyond the realm of science today. In fact, higher education now squarely faces its own crisis of purpose, relevance and future direction.

On 18 June 2025, at the Global Sustainable Development Congress in Istanbul, we reflected on the ten-year journey since the adoption of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). These 17 goals are more than a framework; they are a moral compass, uniting governments, businesses and civil society in pursuit of a sustainable, equitable and inclusive world. For universities, the challenge is twofold: to critically examine our role in shaping the future; and to reimagine our responsibilities within a rapidly transforming global context.

As institutions of higher learning, we hold immense privilege. We generate knowledge, foster innovation and cultivate future leaders. But privilege without purpose is peril.

Professor Chris Brink’s urgent question in "The Soul of the University": What are universities good at, and good for? is more pressing than ever. He advocates for a shift from purely curiosity-driven research to socially-responsive scholarship, deeply rooted in the real challenges of our time. This ethos must begin and end with society.

This vital recalibration is already underway. Professor Letlhokwa Mpedi of the University of Johannesburg is championing a model of ‘societal impact‘. Here, research isn’t an end in itself, but a powerful vehicle for positive transformation.

Similarly, global academic networks, including the Bologna Process group, increasingly emphasize that universities exist to serve society, not just themselves. Research, therefore, must be judged not only by its scientific merit but also by its capacity to advance social cohesion, inform policy and catalyze sustainable development.

The SDGs offer a practical framework for this essential alignment. However, progress remains unequal and far too slow. The 2024 SDGs Report reveals that only 17% of measurable targets are on track for achievement by 2030. This demands a serious re-evaluation of how we conceptualize development, and how we, as educators and institutions, respond.

Here, Amartya Sen’s capabilities approach provides a compelling alternative to simplistic, resource-based models. It urges us to expand real freedoms — the substantive capabilities individuals need to lead lives they value. This means ensuring that our research, partnerships and education systems don’t merely deliver content, but actively enable agency, especially within historically-marginalized communities.

Universities in the Global South must confidently assert their priorities, ensuring international partnerships genuinely support local goals. Concurrently, institutions in the Global North must move beyond extractive models toward more equitable and reciprocal collaborations. Sen’s principle of agency compels us to co-create, not to impose.

Indeed, there is a growing consensus, including one from the 2023 World Economic Forum report, that universities are essential partners in achieving the SDGs. The report outlines actionable steps, including intensifying research into the under-addressed SDGs, forging innovative transnational partnerships, and crafting evidence-based policy solutions grounded in interdisciplinary scholarship.

An example of this is the United Nations University, which, through its global network of multidisciplinary institutes and hubs, bridges research and policy, offering postgraduate education and fostering global collaboration on issues of human survival and sustainable development. Success, therefore, is not defined solely by rankings but by our tangible impact on communities and policy outcomes.

Yet, we must also acknowledge the internal pressures confronting universities: student financing, digital inequality, AI disruption and complex governance challenges. Therefore, sustainability must be both inward and outward-facing. We must not only contribute to global development but also ensure the sustainable development of the university itself.

In a 2017 article, my colleague Bo Xing and I anticipated the emergence of a ‘new university’ — one that is interdisciplinary, virtual, collaborative and deeply integrated into the AI-infused world. What we couldn’t fully predict then was that this would not be a single leap, but a continuum. The paradigm shift we spoke of is still unfolding.

Today, universities aren’t just adapting to change; they are being fundamentally reshaped by it — in real time. To remain relevant, we must embrace this complexity. Our mandate extends far beyond campus walls. As Letlhokwa Mpedi rightly states: “Universities have a responsibility to provide answers”.

Suggested citation: Tshilidzi Marwala. "Higher Education’s Evolving Role in Sustainable Development," United Nations University, UNU Centre, 2025-06-25, https://unu.edu/article/higher-educations-evolving-role-sustainable-development.