When, as an organization, your governance arrangements are compared by the general public to those of FIFA, and FIFA comes out looking good – you know you have a big problem. That is exactly the situation the UN finds itself in now.

Last week, both world bodies faced scandals in which officials elected by around 200 countries were accused of significant corruption. At FIFA, Sepp Blatter, re-elected as President in May 2015, was suspended by a German judge who chairs an independent Ethics Committee set up in 2012 precisely because FIFA has been dogged by such corruption scandals for the last decade. The Committee suspended Blatter for 90 days after the Swiss Attorney-General opened a criminal investigation into suspicious financial transactions involving Blatter and relating to world soccer’s governance. When that 90-day suspension expires, Blatter may face an additional 45 day suspension, all but locking him out of running FIFA until a new presidential election, already scheduled for 26 February 2015, at which he will not stand for re-election.

Unfortunately for world soccer, several of the leading contenders to replace him – including Michel Platini and Chung Mung-joon – have also been suspended. Blatter’s interim successor is Issa Hayatou, who in 2011 was disciplined by the International Olympic Committee for involvement in a bribery scheme; and Platini’s successor is Ángel María Villar – already under FIFA investigation. Indeed, the US has indicted 14 different FIFA officials on corruption-related charges.

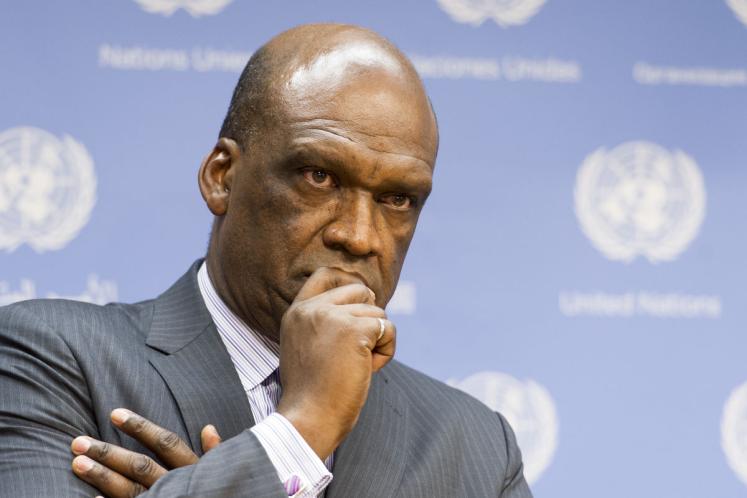

The scandal at the UN was not of the same scale – but at least at FIFA they can suspend their officials when they are suspected of corruption. At the UN, that is not always the case, as became clear over the last week when former President of the UN General Assembly, John Ashe, was arrested on corruption-related charges. Manhattan Prosecutor Preet Bharara suggested Ashe had “sold himself and the global institution he led” by accepting bribes worth more than $1 million. Bharara alleged that while in office as President of the General Assembly, and in return for bribes, Ashe supported a private businessman’s proposal for the construction of a permanent UN conference centre in Macau, even putting the proposal to the Secretary-General.

Some might argue that the position of President of the General Assembly, like the elected offices that convene and preside over other UN intergovernmental bodies, is largely ceremonial – so there is little need for concern about abuse of power or influence-peddling. But these officials have unusually high access to world leaders, and can and do play an important role in brokering political consensus at the UN. The absence of bribery safeguards risks abuse of the office and seriously tarnishing the UN’s public reputation.

Although nothing came of the Macau convention centre proposal, and while Ashe has not held UN office since September 2014, the contrast between what happened at FIFA and what happened at the UN shows just how impotent the UN is in face of such corruption scandals. Ten years ago the Oil for Food scandal led to significant reforms in the ranks of the Secretariat – but not the intergovernmental bodies. Since 2006, the UN Ethics Office has been mandated to run a financial disclosure programme in accordance with the Secretary-General’s bulletin on financial disclosure and declaration of interest statements (ST/SGB/2006/6), to guard against conflicts of interest. This applies to all staff at the Director level and above, and all procurement, investment, and ethics officers. Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon has also encouraged – but not required – senior managers to make their financial disclosures and interest statements public, leading by example. Many other UN senior officials have followed suit.

Yet when Ashe’s arrest was announced, while the Secretary-General pronounced himself “shocked and deeply troubled” by the allegations, which he said struck at “the heart of the integrity of the United Nations”, there was little he could do. Even if Ashe had still been in office, Ban would not have had any recourse over him, since Ashe answered, as President of the General Assembly, to that intergovernmental body, not to the UN Secretariat. (In fact, the President of the General Assembly outranks the Secretary-General in terms of diplomatic protocol, when the General Assembly is in session.) Despite the fact that the PGA receives an office budget (of around $300,000), office space, IT support and security services from the UN, the position of the Secretariat has been that “As to how the member states want to handle and manage the office of the presidency, it’s up to them.”

Still the Secretary-General has moved to do what he can to get the Secretariat’s own house in order. Declaring there can be “no tolerance for corruption at the United Nations,” Ban ordered investigations into two foundations caught in the scandal. One of these – the International South-South Steering Committee for Sustainable Development – found itself in the unfortunate situation of not only having Ashe as a member, but another of the figures in the scandal, the former Dominican diplomat Francis Lorenzo, as its Executive Director. Both were immediately suspended by the Foundation.

Member States have not yet, however, responded with initiatives of their own. And if such a scandal emerged around a sitting President of the General Assembly – or any other leader of the UN’s intergovernmental bodies – there is very little that could be done, as things currently stand. As Transparency International’s Alejandro Salas put it, “you are giving a free pass for an internal lobbyist”. This is why the UN makes FIFA look comparatively well governed.

The UN has no equivalent to FIFA’s independent Ethics Committee in place. The intergovernmental body in question could vote to remove the official, of course, but the result would be precisely that the whole question would instantly become politicized, as Blatter’s reelection as FIFA President was earlier this year. Nothing could be worse for the Organization’s credibility, 10 years after Oil-for-Food, than to have the position of a President of the General Assembly, or ECOSOC, or the Security Council (for that matter) become a bargaining chip in intergovernmental negotiations.

While Presidents of the General Assembly and the UN’s other intergovernmental bodies are paid for their work in the role by the government of the country from which they hail, nothing currently requires disclosure of any further external employment, outside activities, or receipt of gifts or hospitality. Nor is there any formal vetting for the elected positions: the Presidency of the General Assembly is in the gift of the General Assembly – or, really, its regional voting blocs, who get to pick the President on a rotational basis. There are no minimum requirements for the position, and no code of conduct that governs the use of the office. At a time when the General Assembly is pushing for greater transparency and structure in the selection of the UN Secretary-General, the absence of criteria or minimum standards in the election and conduct of their own, notionally more senior leader is stark.

So, what could be done to avoid a FIFA-like meltdown?

The President of the General Assembly and the Member States could quickly put in place an ethics system governing the conduct of elected office-holders in all of the UN’s intergovernmental bodies. (A system just for the General Assembly seems inefficient.) A rigorous 2010 study found that more than two thirds of all countries have parliamentary disclosure laws – and that the presence of such rules correlates to a reduction in public corruption. So there may not be insuperable political obstacles to translating such arrangements to the UN. Nor are such arrangements limited to domestic systems: the President of the European Council, a role analogous to the President of the General Assembly as a president of an intergovernmental body, is subject to a detailed Code of Conduct, covering financial and interest disclosure, gifts and hospitality, and outside activities during and after the term of office. (Unlike the President of the General Assembly, however, the President of the European Council’s salary is paid out of the European Commission budget, not by a Member State.)

Given that the current President of the General Assembly, H.E. Mr Mogens Lykketoft, has signaled his intent to make Good Governance a “priority” of his service in the position, he may wish to consider working with the Presidents of the ECOSOC and Security Council to adopt a Code of Conduct system. Comparative analysis of different national arrangements suggests the basic features of an effective and credible system would include:

-

a general code of conduct outlining expected behavior of elected office-holders;

-

formal and specific ethics rules detailing requirements necessary to fulfill such a code, covering:

-

personal and familial financial and interest disclosure guidelines. Such disclosures may not necessarily need to be made public, so long as they are undertaken prior to or at the time of taking up office, and are available for inspection by rule enforcers. They also need not prevent receipt of a salary from the official’s government;

-

disclosure of gifts and hospitality;

-

disclosure of external employment and outside activities;

-

-

a complaints and regulatory mechanism, with clear and specified sanctioning powers to enforce disclosure and conflict of interest rules, and advise office-holders on conduct issues. There are a variety of models to choose from, ranging from independent external ombudspersons and regulatory commissions, to parliamentary commissioners, to special parliamentary ethics committees. Questions of credibility and independence are crucial. The FIFA story suggests strongly that internal oversight may not be effective, and the involvement of credible external actors, for example with a judicial background, may be necessary to protect an organization’s credibility in the long run.

Of course, no parliamentary Code of Conduct can cure sheer foolishness. In the UK, for example, in July 2015, a Deputy Speaker of the House of Lords, Lord Sewel, resigned after footage emerged that seemed to show him snorting cocaine with two sex workers, despite a notionally strong Code of Conduct being in place. But Codes of Conduct and ethics systems are important to defend the integrity of the system once that foolishness occurs, and to deter abuse of office. Indeed, at first Lord Sewel sought a mere suspension, but when it became clear that expulsion was not only possible but likely under the House’s Code of Conduct, he resigned.

The most important point is to protect the reputation of the Organization. To do that, Member States need to prevent its elected offices losing credibility with the global public by appearing to be treated as patronage assets, which is the view the public seems to have formed of how some FIFA offices are treated. And the Organization needs to be seen to be capable of effective action once abuses do emerge. FIFA’s reputation has suffered not only because its high offices seem to have become prizes to be won, so that influence in the world of soccer could be traded for cash, but also because the system did not seem to be capable of self-correction.

The UN is not yet in FIFA’s position – mocked on American comedy shows. And it should not be allowed to sink so low. The introduction of an ethics system for the leaders of its intergovernmental bodies would be a step in the right direction.

Suggested citation: Dr James Cockayne., "How the UN Made FIFA Look Well Governed – And What the UN Can Do About It," UNU-CPR (blog), 2015-10-13, https://unu.edu/cpr/blog-post/how-un-made-fifa-look-well-governed-and-what-un-can-do-about-it.