When artificial intelligence (AI) is discussed at global forums, Africa is often mentioned but too rarely engaged with, and even less often built with. That imbalance is precisely what the new United Nations University Institute for Artificial Intelligence (UNU-AI), established in Bologna, Italy, in December 2025, seeks to address.

The signing of the Host Country Agreements in Italy marked a turning point for how the United Nations engages with AI. For the first time, the UN system will host an institute designed not only to debate algorithms but also to work directly with them — to experiment, test and learn from real AI systems at the algorithmic level. This shift matters profoundly for the Global South, especially Africa.

For too long, AI governance has been shaped by those who control data, compute, and platforms. The result is a widening global AI divide: while AI drives productivity and innovation in advanced economies, many African countries face constraints in infrastructure, skills and influence over how AI is designed and governed. If left uncorrected, AI risks becoming a new form of dependency rather than a tool for inclusive growth. UNU-AI offers a different path.

During a visit to Silicon Valley, someone once remarked to me, “At international AI governance forums you talk, but in Silicon Valley we do”. That comment stayed with me. Governance without technical understanding is fragile. Regulation without experimentation is blind.

UNU-AI is created to bridge this gap. It is the first entity within the UN system designed to work hands-on with AI algorithms at the source code level, moving from theory to practice, from policy aspiration to applied capability, from an algorithmic perspective. For the Global South, especially Africa, where models trained elsewhere often fail to reflect local realities, this practical engagement is essential.

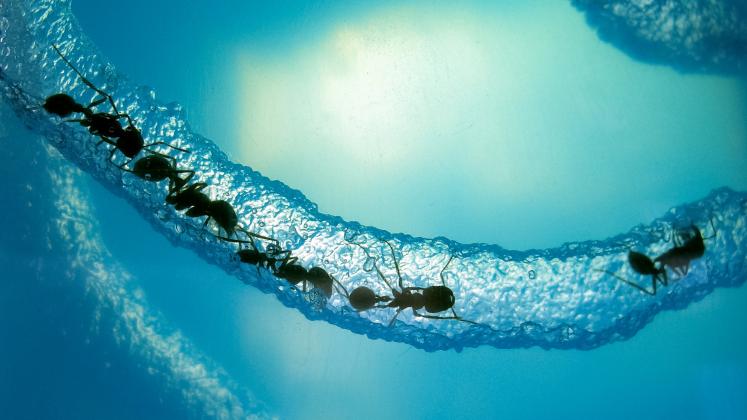

One of the most powerful lessons for inclusive AI does not come from Silicon Valley, but from nature and from a lineage of insight that runs from South Africa’s Eugene Marais to the modern work of Italy’s Marco Dorigo, whose Ant Colony Optimization (ACO) algorithms have shaped contemporary AI. More than a century ago, Marais showed that ant colonies and termite societies exhibit intelligence without central control — individual agents possess limited information, yet through simple local interactions and indirect communication, the collective adapts, solves problems, and remains resilient.

Dorigo later translated these biological principles into computational form, demonstrating that complex optimization can emerge from decentralized coordination rather than hierarchy. This insight is highly relevant to Africa and global AI governance. At a time when AI systems are increasingly centralized around massive datasets, compute, and dominant platforms, ACO reminds us that effective intelligence can also be distributed, adaptive and robust under constraints.

For Africa, it is therefore viable for AI models to work with smaller datasets, operate in resource-limited environments, and be shaped by local knowledge. UNU-AI draws directly on this principle, seeking not to concentrate AI power in one place but to enable distributed innovation by connecting Bologna’s computational capacity with universities in the Global South, research centres and policymakers, allowing knowledge to circulate, adapt and grow locally.

Although UNU-AI is based in Bologna, it is both a European institute and a global hub. It is being designed as a global platform that links advanced infrastructure with regions historically excluded from the center of AI development.

Through joint research programs, visiting fellowships, shared datasets and capacity-building initiatives, UNU-AI will work closely with institutions in Africa, Latin America, the Caribbean and South-East Asia. It will collaborate across the UNU system, drawing on decades of engagement in Africa on development economics, governance, natural resources and sustainability.

The goal is not technology transfer; it is to enable co-creation and the development of AI systems that reflect African contexts, priorities and constraints. Like an ant colony, value is created through many nodes contributing knowledge, rather than through a single dominant hub.

For Africa, access to such infrastructure should be through partnership rather than dependence. UNU-AI enables African researchers and policymakers to engage with frontier AI tools while retaining ownership of development priorities.

UNU-AI is not intended to be just another research center, but its ambition is to become a global ecosystem that connects researchers, policymakers, entrepreneurs and students across regions.

The future of AI will be shaped less by raw computing power than by how intelligence is organized. Ant Colony Optimization teaches us that resilient systems are decentralized, adaptive and inclusive. Africa has a unique opportunity to help define such a future. UNU-AI represents a platform through which global institutions can participate not as spectators, but as co-designers of global AI systems and governance frameworks. If guided wisely, AI can become a force for inclusive growth, resilience and shared prosperity. Connecting Bologna to the rest of the world, including Africa, is not symbolic; it is a strategic necessity for building an AI future that works for everyone.

Suggested citation: Tshilidzi Marwala. "From Bologna To Africa, What Ant Colonies Can Teach Us About Building Inclusive AI," United Nations University, UNU Centre, 2026-02-02, https://unu.edu/article/bologna-africa-what-ant-colonies-can-teach-us-about-building-inclusive-ai.